1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth

Leaf Spring Specifications, Selection, Modification, and Shackles

Introduction

This page discusses the intricacies of leaf spring selection for 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth passenger vehicles that can cause issues when ordering new springs and a design flaw with the original equipment. I began this project after struggling to obtain proper leaf springs for my 1956 Dodge Coronet coupe due to assumptions the spring manufacturer made when I ordered new springs. To save others the hours of emails and phone calls with the manufacturer and my own research and discussing with other enthusiasts, I compiled the spec sheets below using the factory parts manual for car model information and “Leaf Spring Institute” volume 14 published in 1960 for the spring specs. These “stock numbers” are used by current manufacturers such as Eaton Detroit and ESPO Springs. However, there are multiple options for our many models that the spring manufacturers may not analyze long enough to understand, so I created this page to discuss them so others can verify with the manufacturer that they are receiving the desired springs. After addressing spring selection, I discuss a significant design flaw in the original shackle geometry that can be addressed when ordering new springs. Correcting the issue will make for an even smoother ride on the street and will greatly benefit anyone driving curvy roads or using the car on road courses.

My Example of the Leaf Spring Confusion

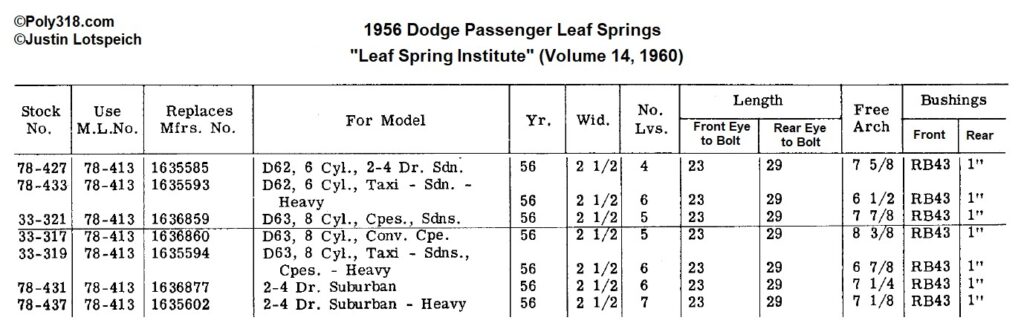

My 1956 Dodge Coronet coupe originally equipped with a 270 hemi-block poly V8 (now a 390 poly A-block stroker) had factory springs Leaf Spring Institute “stock number” 33-321. Figure 4 details that this spring has five leafs with a free arch of 7-7/8″. While the Leaf Spring Institute doesn’t specify the spring capacity, I have verified it is around 710 – 720 lbs each. My car sagged and bounced in the back more than I wanted, which I assumed was because the original springs with 90,000 miles and cracked leafs were trashed. Because I would be using my car on the street and track, I wanted slightly stiffer rear suspension and special-ordered a pair of new springs for a “1956 Dodge Coronet D63-1 club coupe” with factory ride height and requested they add a sixth leaf. It seemed straightforward enough, but that order began a two-month long adventure.

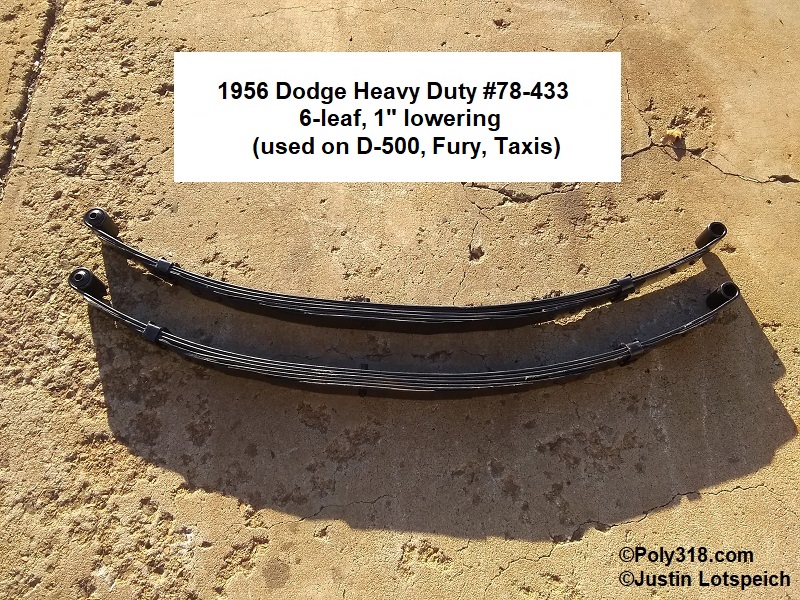

The leaf springs I received looked great, but once I got them installed I was puzzled why the ride height was 1″ lower than the old springs and they were not much stiffer than the old springs. After multiple emails and telephone calls with the spring manufacturer and after I located the Leaf Spring Institute manual and compared it to the factory parts manual, I discovered the problem. Rather than building a spring #33-321 (Figure 4) correct for a 1956 Dodge Coronet V8 club coupe and adding a sixth leaf as I ordered, the manufacturer simply went down the “number of leafs” column, found a 6-leaf version for a V8 coupe, and built it. The mistake here stems from the manufacturer not paying attention to the free arch dimension. They had built and sent me a #33-319 spring that has 1″ less arch (6-7/8″) than the 1956 Dodge Coronet club coupe (7-7/8″). This particular spring was used on 1956 Dodge hemi D-500 and taxicab models and on 1956 Plymouth Furys; it was paired with shorter front coil springs in order to lower the performance models for better handling during racing and to lower taxicabs for ease of passenger entry. The sixth leaf on these springs brings their capacity to around 760 lbs. each and is designed to compensate for less arch (which decreases the spring capacity), stiffer suspension for racing in the D-500 and Fury, and for additional taxicab passenger/luggage weight capacity. The issue with the sixth leaf is that it is the shortest leaf that mates to the axle spring perch, so it doesn’t do much over the soft factory ride. (Of note regarding this D500/taxi/Fury leaf spring, early production identified the spring as part number 1675690 but quickly changed the number to the 1635594 that correlates with the “stock number” 33-319).

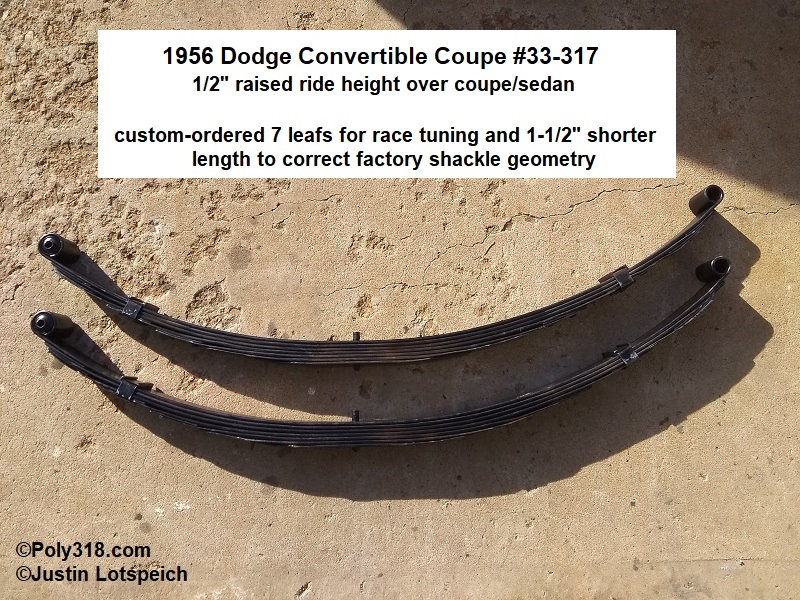

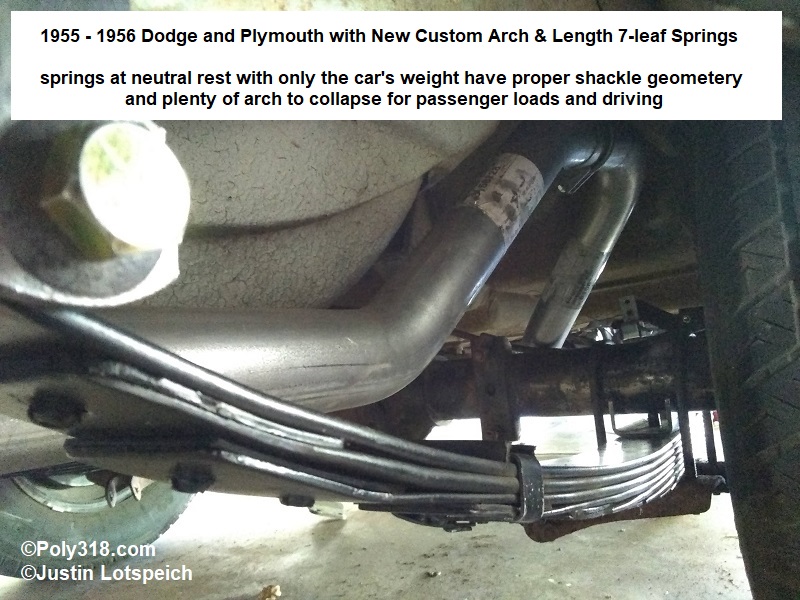

Once I explained the arch/ride-height and soft spring-rate issues to the manufacturer, they agreed to build me a new set since they admitted they hadn’t built the springs to my specifications. Improving the new springs based off my feedback, we decided on adding a seventh leaf that would go under the top leaf (with the eyes) and would extend under the eyes to better support/double up the top leaf. We also decided on an 8-3/4″ free arch to provide a higher load capacity and spring rate, ensuring the spring would not go flat at neutral rest and would stiffen the ride. Due to my experience, my recommendation for those ordering leaf springs is to use the “stock numbers” in Figures 3 – 6 to ensure you are receiving the specifications you desire and then make any custom modifications to the order. For example, if you want a little more rake and higher spring capacity in the back of your coupe or sedan, you might order a #33-317 original used on convertibles.

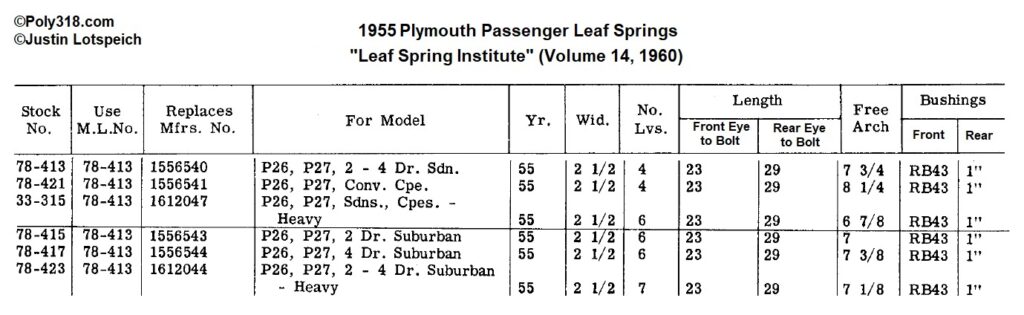

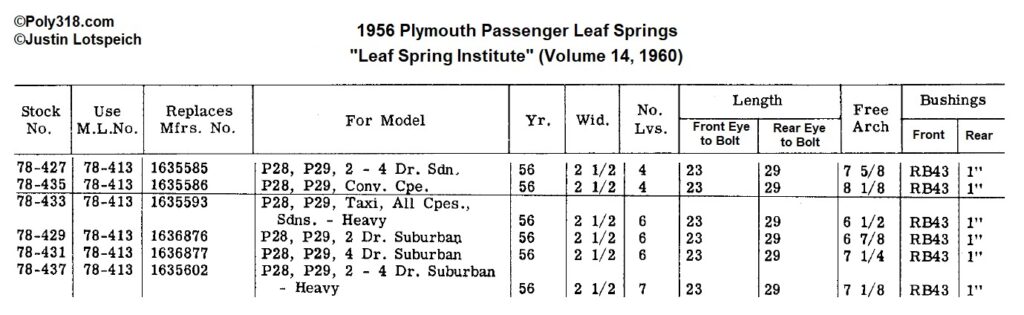

Tow and Heavy Load Vehicles

For vehicles that will see heavier loads (passengers/luggage) and towing, suburban springs are options worth reviewing, although my experience above suggests even the factory suburban springs will sag badly when towing since they have lower arch from the start. All 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth suburbans have an optional 7-leaf spring 78-423 or 78-437, which are identical springs even thought he part number changes between 1955 and 1956. According to spring manufacturers, this spring has a capacity rating of around 1,000 lbs. Keep in mind that if used on a coupe or sedan, the ride height will decrease by 3/4″ over the factory spring unless additional arch is built into the spring. For cars that might tow a small camper trailer or race car, I would be more inclined to order a 78-437 springs with another inch if not two of arch built in and additional leafs, which would both increase the spring capacity and spring rate. The spring manufacturer can calculate the necessary quantity of leafs in relationship to the desired free arch and needed towing capacity.

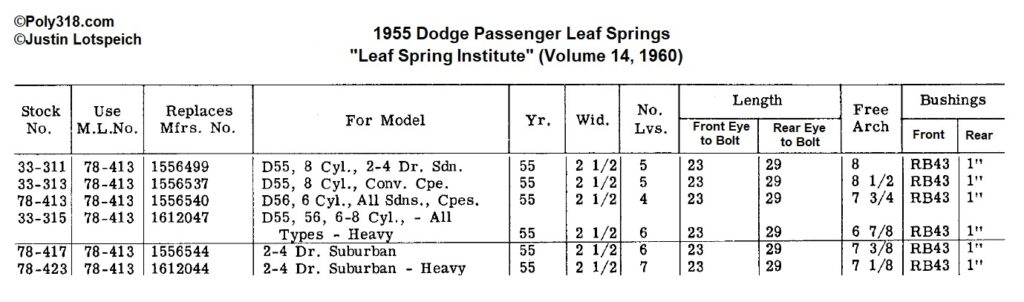

Leaf Spring Institute Specifications

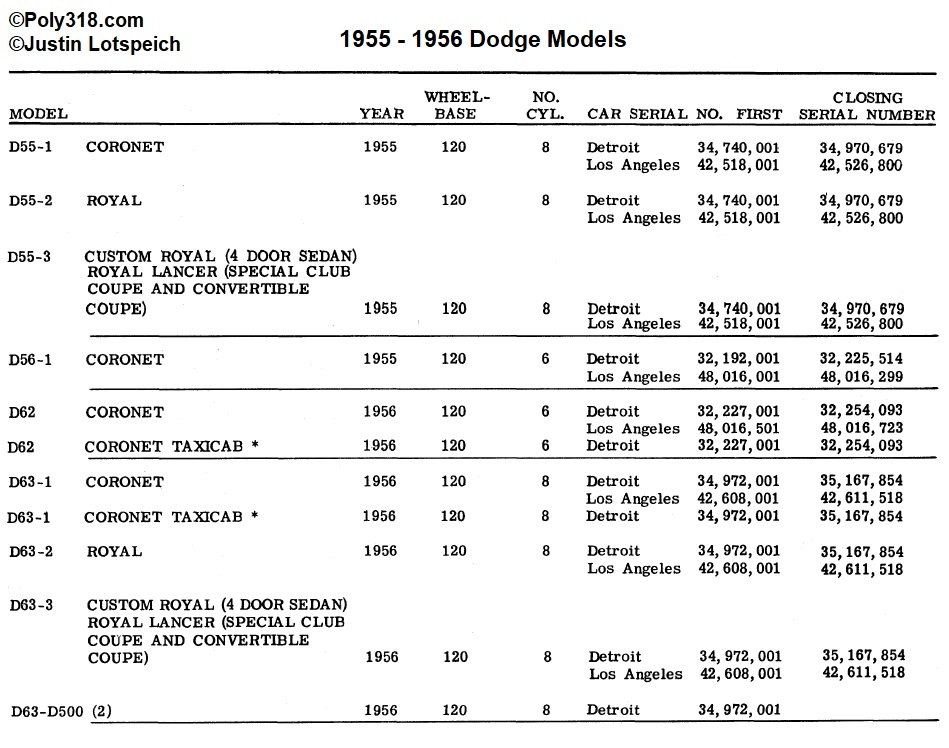

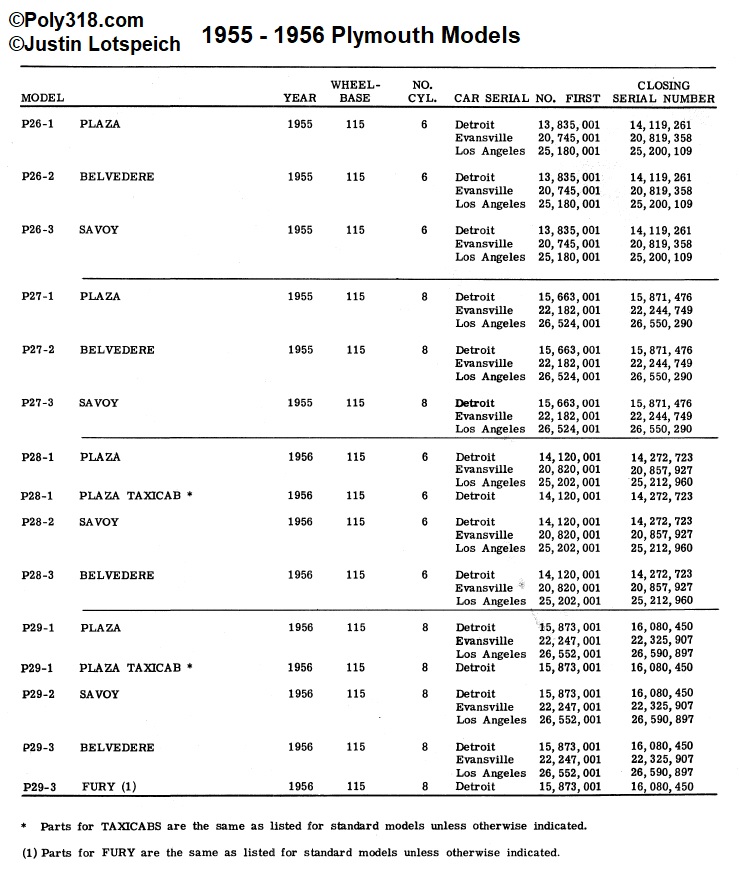

In Figures 1 and 2, I provide the model information from the factory parts manual since the Leaf Spring Institute includes some of these details, such as “D63” and “P28.” Unfortunately, the Leaf Spring Institute details delete the sub-models, such as D63-2 and P29-3, which may be helpful for those trying to locate springs for specific model cars. Figures 3 and 4 pertain to 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Figures 5 and 6 cover 1955 – 1956 Plymouth. Note that in many cases, the differences between 1955 and 1956 and between Dodge and Plymouth are negligible to where there are many interchange options. For example, the difference between a #33-311 for a 1955 Dodge Coronet coupe and #33-321 for a 1956 Dodge Coronet coupe is 1/8″ of arch.

Design Flaw in Original Leaf Spring Shackle Geometry and Load Capacity

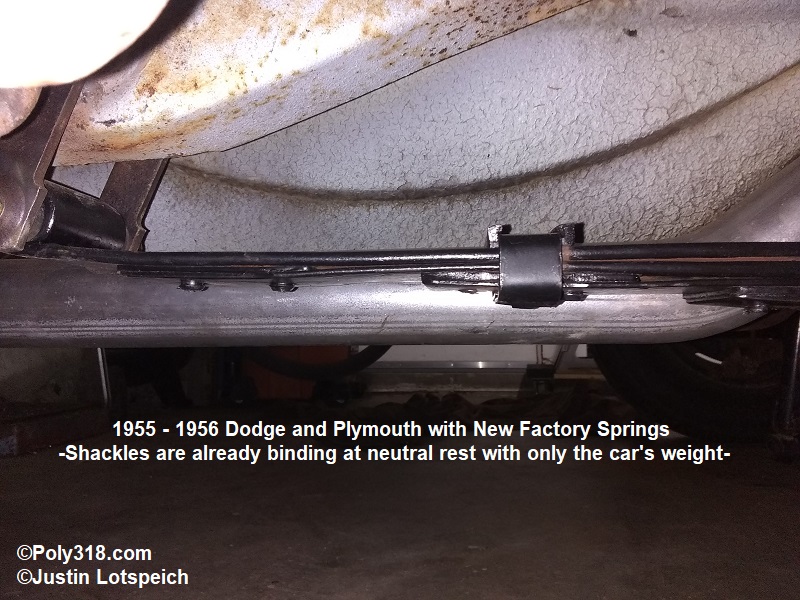

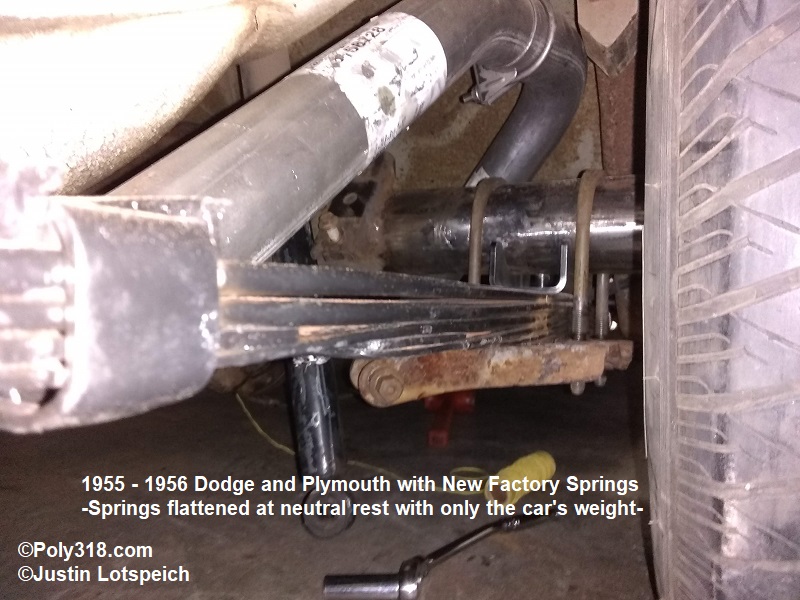

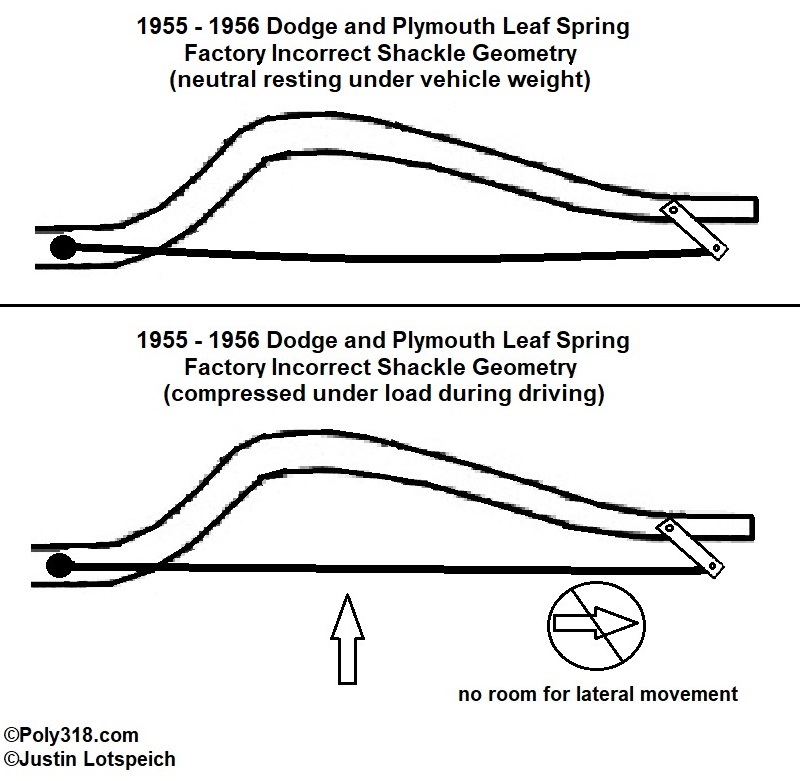

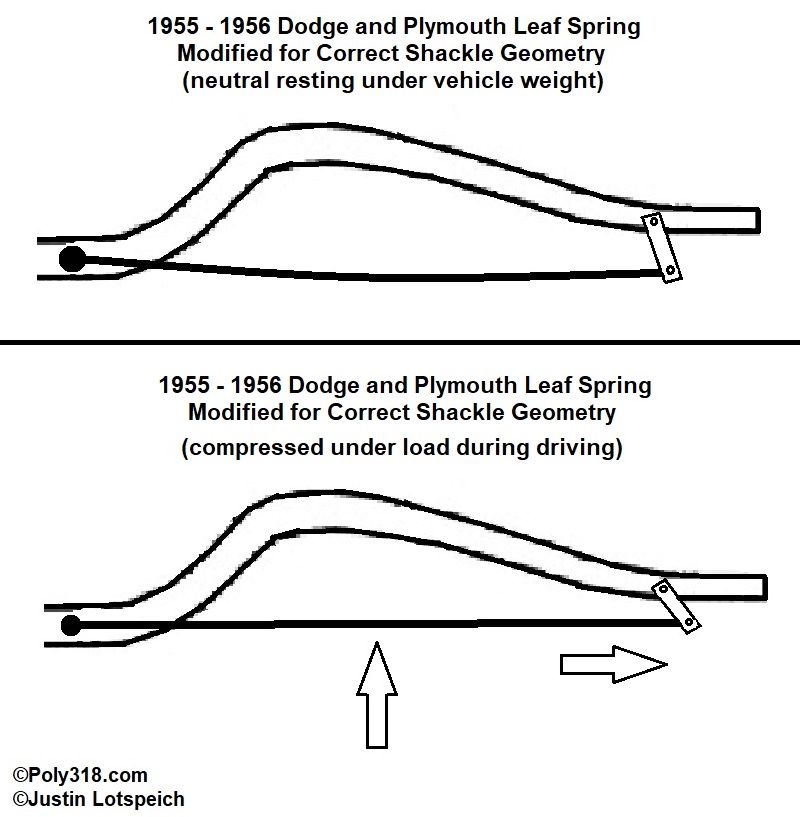

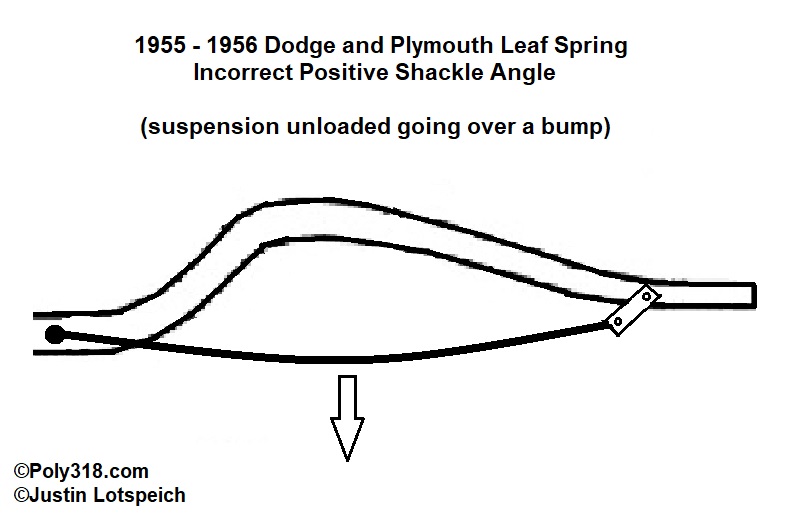

1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth passenger cars have significant design flaws in their shackle geometry and load capacity. Depending on how you approach the shackle issue, either the leaf spring is too long eye-to-eye or the chassis shackle boss is placed too far forward. The front spring eye is fastened to the chassis to where it cannot move laterally and only rotate on the eye bolt. The rear spring eye should be hinged via the shackle, allowing the leaf spring to flatten and arch as the chassis is loaded and unloaded during driving. Figures 7 – 8 show stock 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth rear suspension neutral at rest under the vehicle’s weight. From the factory, brand new springs rest almost flat with practically no arch. Notice the angle of the shackle is swung at a drastic angle back and up toward the chassis to where it is already binding, as in it has no room to swing back and up to absorb and therefore cushion additional load from passengers or during driving. The factory angle essentially fastens the rear eye to the chassis similar to the front, leading to more road vibrations/bumps being felt by the occupants since the bound shackle counters the spring’s desire to flatten out and become longer from eye to eye. At the same time as the shackle geometry issue, the the springs are too weak being flattened out where as passengers and luggage are loaded and as additional loads are pressed down onto the spring during driving, the ride bounces more as the spring is forced to go negative in arch and want to spring back flat. For an actual visual of the issue, look at your spring shackle while someone bounces on the rear bumper, and you’ll see the shackle does not swing back and forward to absorb the load, and all the movement comes from the spring going into negative arch.

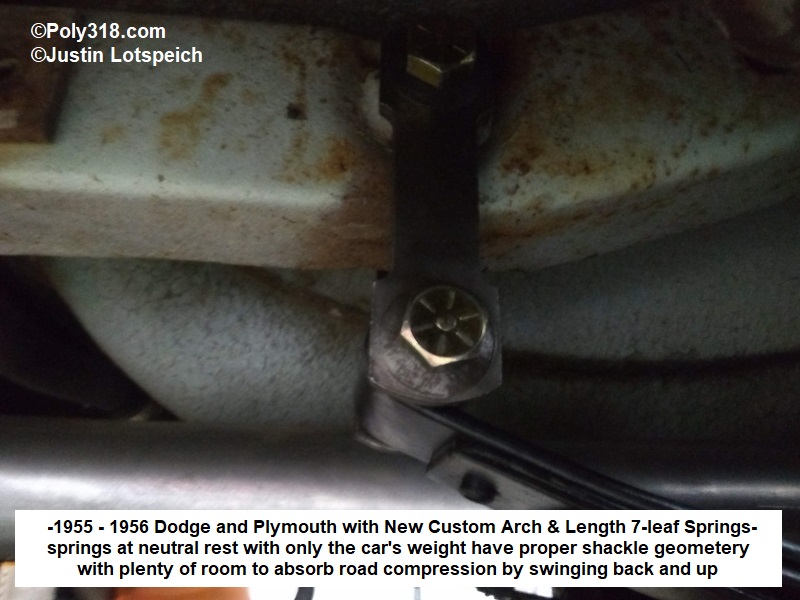

The easiest way to correct the design flaws are to use shorter leaf springs and more leafs, which is easy to do if you are already ordering new springs. All factory 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth springs are 49″ long eye-to-eye unloaded at free arch. When I ordered new springs for my 1956 Dodge coupe, I had the manufacturer make them 47-1/2″ eye-to-eye unloaded and with seven leafs for better spring rate with the second spring from the top extending under the first leaf’s eyes for better support. These modifications brought the shackle angle to a correct plumb orientation and allowed the spring to maintain a healthy arch as seen in Figures 9 – 10. A crucial consideration here is that the shackle is almost plumb with a 1° negative angle (leaf-spring eye farther toward the rear than the chassis connection) so that the shackle more naturally wants to swing back and up under road loads. If the leaf spring is too short, the shackle will have a positive angle (leaf-spring eye farther toward the front of the car than the chassis connection), resulting in a stiffer ride since the spring has to work harder flattening out to overcome the shackle’s plumb line before being able to swing back and up (Figure 10). Note that with my custom 47-1/2″ spring design, the shackles will look like Figure 10 when the chassis is supported by jack stands and the rear axle is dangling completely unloaded. The 47-1/2″ custom springs also required me to use a C-clamp to lightly compress the front spring eye bracket up against the chassis bracket in order to start the four bolts.

The last caveat for correcting the shackle geometry with shorter leaf springs and more leafs is that ride height will be modified. The factory configuration has the rear spring eye very close to the bottom of the chassis and the spring flat. As the leaf spring is shortened eye-to-eye to correct the shackle angle, the rear eye swings down away from the chassis, which will raise the ride height. The addition of two leafs maintains arch in the spring and, thus, increases the ride height as well. With my 47-1/2″ long custom springs and seven leafs compared to 6, the ride height raised 2″ over the stock configuration. For my aesthetic goal, I wanted more rake to the car over stock, so this increased rear ride height was desired to where my front rocker panel now sits 10″ off the ground and the rear rocker just before the wheel opening 12″. If you want to maintain the factory ride height, you need to have the spring manufacturer reduce the spring free arch by the amount the shackle moves down away from the chassis (1″ in the case of my 47-1/2″ springs). Keep in mind that as arch is taken out of the spring, the spring capacity decreases too, so it would be wise to have the spring manufacturer add an additional leaf to maintain the desired spring capacity.

Leaf Spring Shackle Rebuild

Oftentimes the 1955 – 1956 Dodge and Plymouth shackle bolts will be heavily corroded and should be replaced. While new factory style shackles are still available through some spring manufacturers at the time I write, they are expensive at about $100 including bushings for what you get. I rebuilt my shackles in an hour for $30 including bushings. The rebuilt shackles that use removable bolts are also easier to install and remove than the OEM style.

- Press out the shackle bolts from the bars either using a hydraulic press or large vice. If using a vice, back the head of the bolt with a piece of round stock or socket to allow the bolt to compress out of the bar. Depending on the shackle’s corrosion, the bolts can be extremely difficult to press out even with heat and penetrating oil. If the pressure required to press out the bolt threatens to bend the bar, don’t bother using heat and instead grind off the bolt head and use a drift to punch out the bolt.

- Drill out the serrated holes to 9/16″ and chamfer the edges to remove any burrs.

- Drill out the smaller holes on the inner bars to 9/16″ and chamber the edges to remove any burrs.

- Clean off any corrosion/debris from the bars and paint as desired.

- Obtain four grade eight 9-16″ by a minimum of 4-3/8″ length of shank (course or fine thread) and four nylock nuts (the nuts can be any grade).

- Obtain eight Moog K7308 rubber bushings that are used for both the chassis boss and leaf-spring eye.

- Lightly lubricate the bushing inner holes and bolts with a grease that won’t eat rubber, such as silicone grease, to help the shackles swing smoothly and to protect the bolts from corrosion.

- The original shackle nuts compress the inner bar against the bolt shoulder, which the rebuilt shackle bolts don’t have. Simply tighten the nylock nuts until the bushings gently compress and there is no slop when rocking the leaf spring side to side. Too tight will create binding and wear the bushings quicker, and too loose can create noise and wear the bushing quicker.