Poly Crankshafts, Transmissions,

and Adapters

(applicable to 277, 301, 303, 313, 318, and 326 engines)

Introduction

Invariably, a poly 318 and other A-block needs a crankshaft and transmission. The poly A-block went through a design change that needs to be considered when selecting both the year of engine and the type of transmission for a vehicle, which also applies to Gen I Hemi and Hemi-block polys. Because of the inseparable nature of the crankshaft and transmission, I discuss them both in this article. I cover crankshaft options, PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmissions, A833 manual transmissions, and NV3500, NV3500HD, and NV4500 transmissions. I also address the often-overlooked process of aligning the bellhousing/input shaft with the crankshaft centerline.

Poly A-block Crankshafts

Contrary to some rumors online, all A-blocks from 1956 – 1967 are internally balanced just like the LA 273, 318, and forged-crank 340. The LA360, Magnum 360, and cast-crank 340 are the only externally balanced Mopar small blocks. I surmise that some of the confusion stems from people calling the harmonic damper a “balancer” and that truck and manual-transmission engines did not use a damper but a deep pulley instead. These differences seem to have some people think the engines with the deep pulley are internally balanced and the engines with the damper are externally balanced, but, again, all A-blocks are internally balanced.

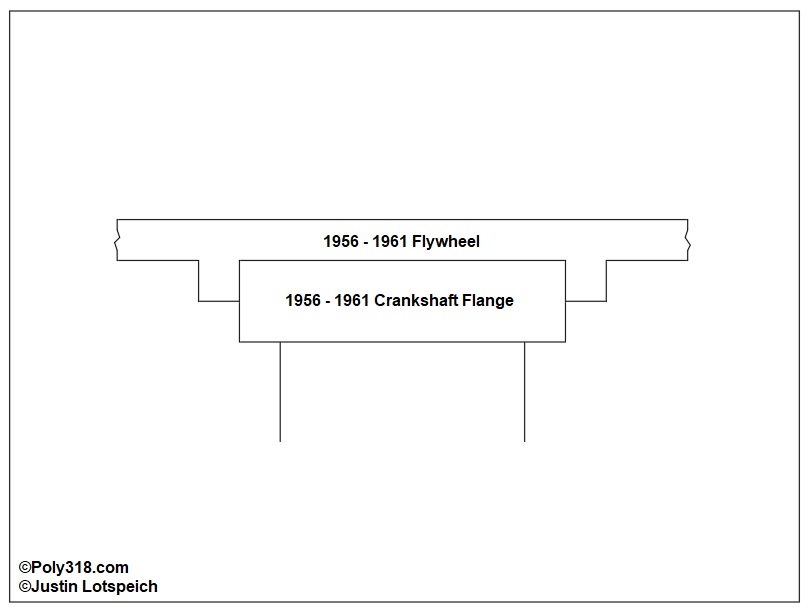

1956 – 1961 A-block crankshafts have a 0.5″ longer rear flange and 8 bolts to mate to cast iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmissions using a factory spacer plate (Figures 1a – 1d). A 1962 onward aluminum TorqueFlite, A833 bellhousing, and Magnum NV3500 or NV4500 will not bolt up to a 1956 – 1961 crankshaft without an adapter, which I detail in a section below.

The Gen I Hemi (e.g. 331, 354, 392, etc.) and Hemi-block poly (e.g. 270, 315, etc.) crankshafts do not interchange with any A-blocks.

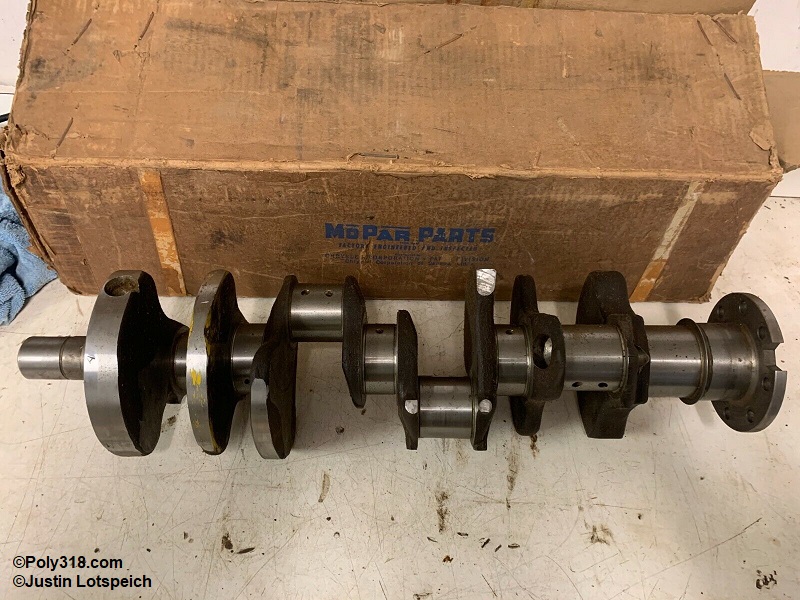

1962 – 1966 A-block 313 and 318 use the same crankshaft forging as an LA 273/318/340 and has a 6-bolt flange. A great benefit of the poly 318 is that all factory crankshafts are forged, whereas factory LA crankshafts were forged up to 1972 and then cast from 1973 onward. Note that you can physically bolt a 1962 onward crankshaft into the 1956 – 1961 block, but the crankshaft rear flange will be too short to mate to pre-1962 iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmissions without a spacer.

Parts Interchange and Rotating Assembly Balancing Requirements

It is acceptable to swap rotating assembly parts (crank, rods, pistons) that weigh within plus or minus 1 gram of each other without requiring balancing the rotating assembly, keeping in mind that the rods should be weighed using a jig to measure the weight of each end. For most A-blocks, a machinist will want to see no more than what’s called 2 oz-inch of difference during balancing, which is not the same as simply weighing parts and guessing. Also, one must be be vigilant of stacking tolerances. Stacking tolerances takes into account the sum of tolerances. For example, if every component is at the maximum of the allowable tolerances, when added up, as in “stacked,” the weight may throw the assembly out of tolerance. If components fall outside plus or minus 1 gram, they need to be addressed to balance the assembly, which may also include removing or adding weight to the crankshaft. Swapping in any other crankshaft (LA 273, 318, 340, or aftermarket) into an A-block requires a machinist checking and likely balancing the rotating assembly since A-block piston weight differs significantly from the LA pistons. When swapping connecting rods, keep in mind that Mopar changed the design from the earlier A-block lightweight rods to a heavier forging. Neglecting to properly balance a rotating assembly will create vibrations, rob power, limit the rpm range, and may lead to engine and transmission parts failure.

Poly Engine Blocks

In relationship to the two crankshaft designs, the 1956 – 1961 A-block block is different from the 1962 – 1966 block. The 1956 – 1961 blocks share the same bellhousing bolt pattern and alignment dowel configuration as the Gen I hemi and hemi-block polys except for the 1951 – 1953 Chrysler 331 “extended block” (Figures 2a – 2b). While the 1956 – 1961 A-block has a similar bellhousing bolt pattern to the LA, the alignment dowels are in completely different locations. Since the alignment dowels are critical for proper crankshaft-to-input-shaft alignment, they cannot simply be pulled out and discarded to make an LA bellhousing work.

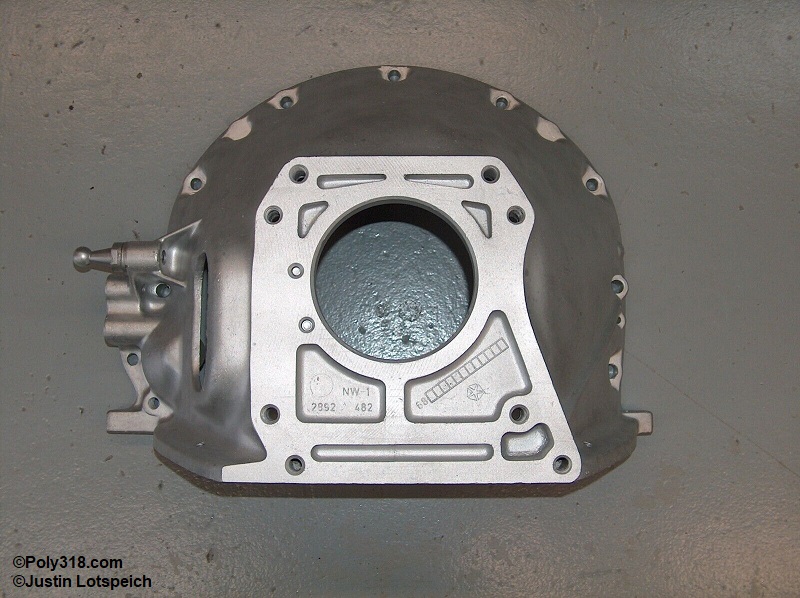

1962 – 1966 A-block blocks share the same bellhousing bolt pattern and alignment dowel configuration as LA engines and Magnum engines, with the exception of one bolt missing for the Magnums (Figure 2c). Note how the LA alignment dowels are higher and farther out than the 1956 – 1961 block.

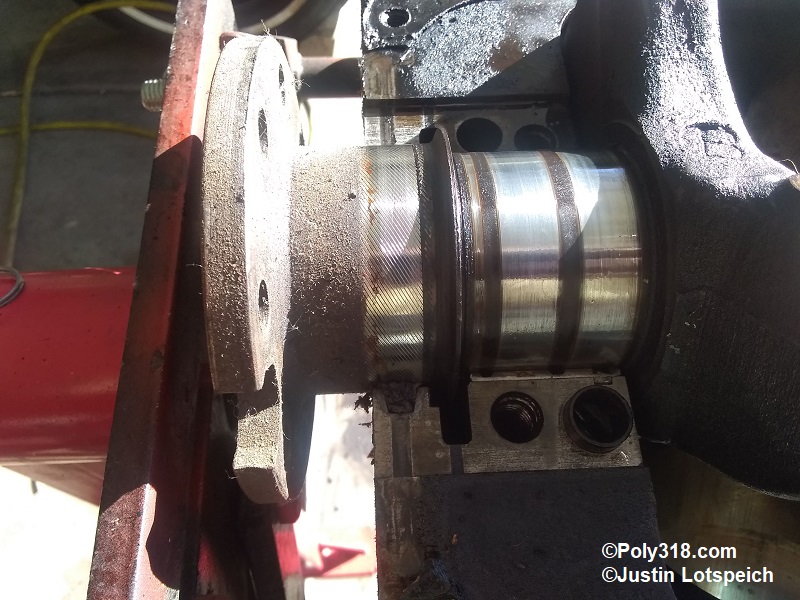

Crankshaft Pilot Bearing and Converter Snout Machining

We now must deal with the torque converter snout or pilot bearing machining. When swapping transmissions and/or crankshafts, attention must be paid to the crankshaft rear flange machining. Automatic 1956 – 1961 crankshafts have large, deep chamfer in them (Figure 2a above) that makes installing a conventional pilot bushing impossible. All 1962 – 1967 A-block and LA crank flanges were machined with a 1-3/4″ diameter hole to accept the TorqueFlite 904/727 small-diameter converter snout (Figure 3a) with a smaller hole inside for the standard-transmission pilot bearing. Manual-transmission crankshafts had the pilot-bearing hole machined deeper and with a more accurate bore diameter to accept the pilot bearing (Figure 3b). Figure 3a shows an automatic crank’s bore that I confirmed with a caliper is 1/8″ shallower than the standard crank in Figure 3b to where the pilot bearing would protrude and bind on the input shaft if I attempted to run this crankshaft with a standard transmission. Keep in mind that many automatic cars ended up with crankshafts machined for standard transmissions since the factory used what parts they had on hand.

Figure 3c details the machining requirements if an automatic crankshaft needs to be machined to accept a pilot bearing. An alternative is to use a Magnum pilot bearing SKFB287 or 4338876 (Figure 3d) that presses into the torque converter snout well, but input shaft clearance should be checked and the crank drilled out if clearance is needed. Some people recommend cutting off the input shaft, but I would not because it is an unnecessary workaround that will make using the input shaft in a non-Magnum pilot bearing weaker. The bushing version in Figure 3d is preferred to the needle bearing version FC69907 (Figure 3e) because some people report needle bearing failure in performance builds that can chew up the input shaft.

In 1968, Mopar changed the TorqueFlite from 19 to 24 input splines on the 727, 18 to 27 input splines on the 904, and a larger diameter converter snout on both. Consequently, 1968 onward LA crankshaft flanges are machined to accept a larger pilot bearing (Figure 3f), although the cranks retain the 1-3/4″ diameter hole for the converter snout. To make matters worse for the pre-1968 transmissions, the small pilot bearings are getting hard to source new, and torque converter stall selection for 19-spline input shafts is extremely limited and expensive compared to the 1968 and later 24-spline shafts. One fix particularly useful for those running cable-operated TorqueFlites is to install a 1968 or later 24-spline non-lockup input shaft in the 1962 – 1967 TorqueFlite to accept the wider range of later torque converters; review my TorqueFlite technical article to see what parts are needed for the conversion since there was another design change that impacts the conversion. For those interested in an aftermarket LA crankshaft, they are machined for the larger pilot bearing.

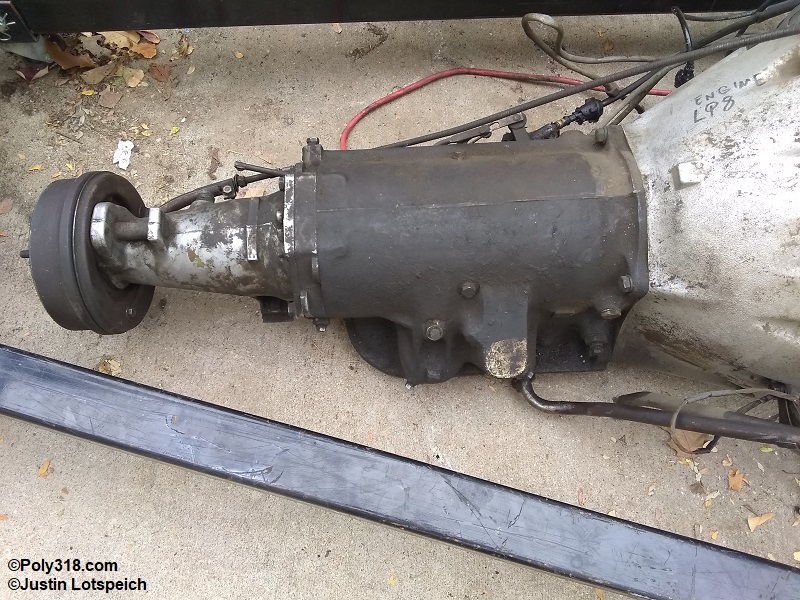

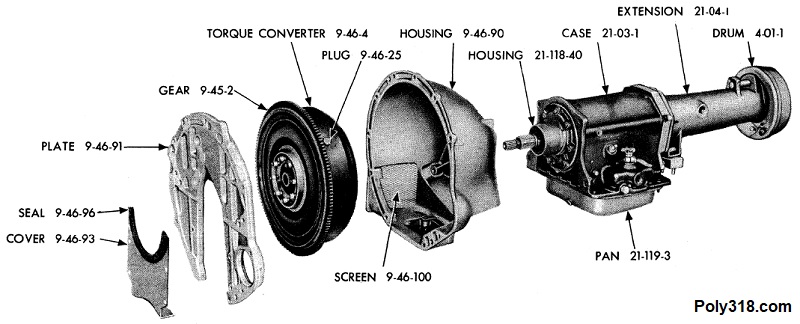

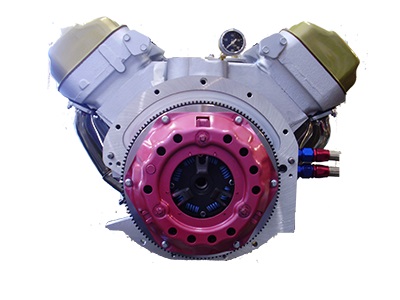

Automatic Poly 277, 301, 303, 313, 318, 326 Transmission Options

1956 – 1961 A-blocks accept iron two-speed PowerFlite and iron three-speed TorqueFlites found on 1956 – 1961 A-blocks, Hemi, and Hemi-block poly engines (Figures 4a – 4b). I detail the PowerFlite and TorqueFlite options in the transmission guide. Due to changes throughout the years including moving from air-cooled to oil-cooled, the bellhousing, torque converter, engine plate, and cover should match in type (Figure 4c). Gary Stauffer with Quality Engineered Components, Hot Heads, Wilcap, and TR Waters makes adapters to fit 1962 onward automatic TorqueFlite 727, 904, 998, 999 transmissions to a 1956 – 1961 block, although they are often only advertised as Hemi adapters. There is no adapter available to mate a pre-1962 iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmission to a 1962 – 1966 A-block.

1962 – 1967 A-blocks accept both A-block and LA aluminum Torqueflite 727, 904, 998, and 999 transmissions, which I details at great length in the TorqueFlite guide. Note that using the 904 may require clearancing the block at the starter motor, which should be mocked up and scribed before machining.

Flexplates

1956 – 1961 A-blocks have the starter ring gear attached to the torque converter; the torque converter needs to match the transmission being used.

All 1962 onward A-block and LA 273/318/forged-crank 340 flexplates interchange and are neutral balanced. LA360 and cast-crank 340 flex plates may be weighted to balance the rotating assembly, although some were neutral balanced when the converter was weighted. If using an LA360 or cast-crank 340 felxplate, it should be confirmed to be neutral balanced, although it’s safer to simply purchase a neutral flexplate.

A833 Manual Transmission to Poly 277, 301, 303, 313, 318, 326 A-blocks

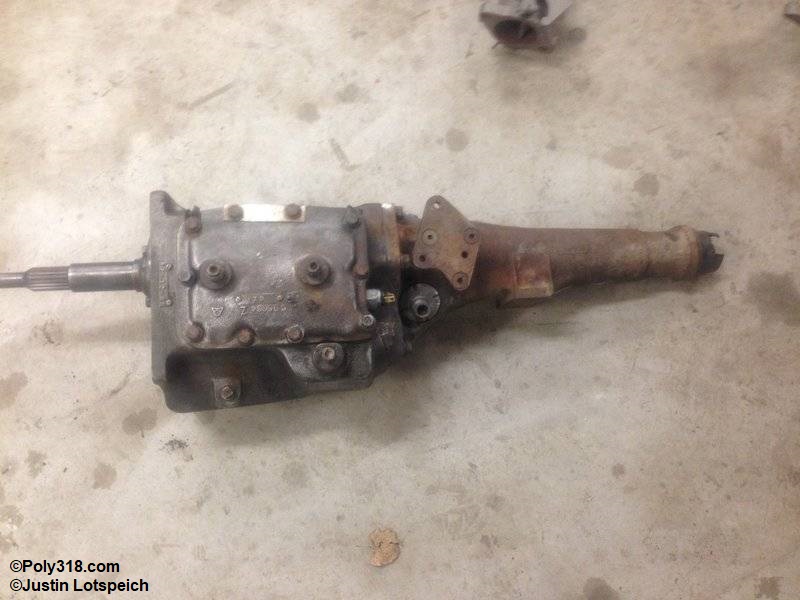

In 1964, Mopar began using the New Process Gear Company “A833” four-speed manual transmission that would become the go-to manual transmission for economy, light truck, and high-performance vehicles through the 1980s (Figure 5a). In 1975, the overdrive version was introduced. Due to the intricacies of each application, I break up components first while weaving in discussion of using the A833 in 1962 – 1967 A-blocks; I summarize the 1962 – 1967 conversion and then address retrofitting 1956 – 1961 A-blocks with an A833 in their own sections.

A833 Input Shaft Bearings and Retainers:

Non-overdrive A833 either have a 4.354” diameter bearing retainer for the #307 bearing (part 4529698) or a 4.807″ retainer for the larger #308 bearing (part 4529699) used on the 426 Hemi and high-performance 440 versions (Figure 5b). All 4.354″ retainers have a bolt circle of 3.70″ (casting 4529694), the 1968 – 1969 B/RB 4.807″ retainers have a bolt circle of 3.70″ (casting 4529695), and the remaining 4.807″ retainers have a 4.16″ bolt circle (castings 4529696 and 4529698). The bellhousing has a corresponding hole to fit either the smaller 4.3” or 4.8” retainer, and one should be extremely careful to ensure the retainer and bellhousing are not mixed up since using the 4.3” retainer in a 4.8” or 5.125″ (discussed next) bellhousing will cause major crankshaft-to-input-shaft misalignment since the transmission will rely on the four mounting bolts to center it, which creates too much slop and therefore runout. The smaller 307 bearing and 4.3” retainer and bellhousing can be converted to a 308 by machining the bellhousing to 4.805” and using a 308 bearing and 4.8” retainer.

The 1975 – 1987 overdrive A833 has the largest 5.125” bearing retainer and uses the 307 bearing on early production models and 308 bearings on the rest. The bellhousing has a corresponding large hole to accept the retainer, and the overdrive bellhousings are designed for the clutch fork and shifting linkage system specific to overdrives.

A833 Bellhousings:

All factory and aftermarket LA bellhousings and scatter shields will bolt up to a 1962 -1967 A-block engine and crankshaft including the earlier iron and aluminum 4.354″ (Figure 5c). The more plentiful (still sitting in many salvage yards) 1975 – 1987 LA318 and LA360 car and light truck aluminum overdrive bellhousing with its 5.125” bearing retainer hole (Figure 5d)can be adapted to the non-overdrive A833 with a 4.3” diameter bearing retainer. A special ring can be pressed into the 5.125” retainer hole to decrease the diameter to the 4.8″ or 4.3” retainer.

Alternatively, the transmission can be modified to fit the bellhousing. Aftermarket suppliers like Brewer’s Performance sell retainers to convert from a 307 bearing and 4.354” retainer to a 308 bearing and 5.125” retainer.

Lastly, the guts from a non-overdrive A833 can be installed in an overdrive case for use with the overdrive 5.125” bellhousing.

If anyone is wondering, the Slant 6 bellhousing is completely different and cannot be used on an A/LA engine.

A833 Flywheels:

A 10.5″ clutch 130-tooth flywheel for the 1962 – 1967 A-block can be sourced from most internally balanced LA, B, and RB engines and purchased new in both cast and SFI-approved billet (Figure 5e). The outliers are that 1964 – 1968 LA273 and LA318 can have a smaller 9.5” clutch and 122 teeth. LA360 and the cast-crankshaft LA340 are externally balanced with a weighted flywheel that should not be used with the internally balanced A-block. The Slant 6 flywheel uses a 9.5” clutch and 122 teeth and should be avoided.

A833 Output Shaft and Tail Housing:

The A833 output shaft and tailhousing come in a short version for A and F bodies and a couple different long versions for B, C, and E bodies. The shifter mounting pad configuration changed with these tailhousings and should be considered for crossmember and shifter placement in the vehicle along with other restricting factors such as torsion bars. The short tailshaft has the shifter mounting pad near the rear of the tailhousing configured for A and F bodies; the longer tailhousing has either a single shifter mounting pad near the front of the housing for B and C bodies or a shifter mounting pad at the front of the tailhousing for B bodies and a second pad at the rear for E bodies. 1964 – 1965 transmissions used the smaller cable-attached speedometer gear pilot, while 1966 onward use the larger adjustable speedometer housing.

1964 – 1965 A833 uses a fixed output flange to accept the ball-and-trunion driveshaft, whereas the 1966 onward A833 uses a splined output shaft to accept the driveshaft’s slip yoke. Aside from the extremely coarse splines, the 1964 – 1965 output shaft is identifiable by the threads on the end of it.

While the majority of 1966 – 1987 A833 use the larger 30-spline output shaft diameter used on the TorqueFlite 727, some mid-1960’s and mid-1970’s A833 used the smaller TorqueFlite 904 splines.

A833 Clutch Forks, “Z” bars, and Shifter Linkage:

Mopar used different clutch fork, Z bar, and shifter linkage configurations throughout the years and depending on the application, so it is important to match the configuration to the bellhousing year/model.

A833 in 1962 – 1967 Poly 313 and 318 A-blocks (applicable to most LA 273, 318, 340):

I know this article has a lot of information in it, so I want to briefly summarize the process of converting an automatic 1962 – 1967 A-block to an A833; the process is pretty straight forward so long as one checks all the components for comparability. Any A/LA 1962 – 1987 iron or aluminum A833 bellhousing or aftermarket scatter shield can be used keeping in mind body clearance. Any 1964 – 1974 non-overdrive or 1975 – 1987 overdrive A833 can be used whether iron or aluminum case. The transmission’s input bearing retainer diameter must match the bellhousing hole diameter with the option of modification as discussed above. Aside from the 1964 – 1965 A833 with the fixed output flange, mostly all other A833 accept the 30-spline slip yoke. For vehicles where the shifter lever needs to be farther forward, use an A-body short output/tailshaft or a B/C body or dual-pad B/E long tailshaft; for vehicles where the shifter lever needs to be farther back, use the dual-pad B/E long output/tailshaft. It is easiest to match the clutch fork and linkage configuration to the bellhousing year/model since the pivot and fork configurations changed throughout the years. Any factory or aftermarket cast, billet steel, or aluminum 10.5″ clutch, 130-tooth, 6-bolt, neutral balanced flywheel for an A, LA, B, and RB engine will work. The A-block crankshaft flange should be checked to ensure it is machined to accept the pilot bushing; if it is not finish-machined, a machinist will either need to do the final machining, or a later converter-hub bushing/bearing insert can be used. Don’t forget to measure and adjust crankshaft-to-input shaft alignment once the bellhousing is mocked up onto the block, which I detail below.

A833 in 1956 – 1961 Poly 277, 301, 303, 313, 318, 326 A-blocks (applicable to most Gen I Hemi and Hemi-block Poly):

Fitting an A833 to a 1956 – 1961 A-block is either not for the faint of heart or not for the light of wallet since those doing the work themselves will put a lot of time and effort into the process, and those paying someone else to do the work will pay a premium for custom adapters and machining. After reading through the intricacies I go over below, one can see it’s far from straightforward or inexpensive compared to converting a 1962 – 1967 A-block. For the money involved, it might even be more economical to replace the pre-1962 A-block with a 1962 – 1967 engine and take advantage of all the LA engine and transmission components that interchange and are readily available new and used.

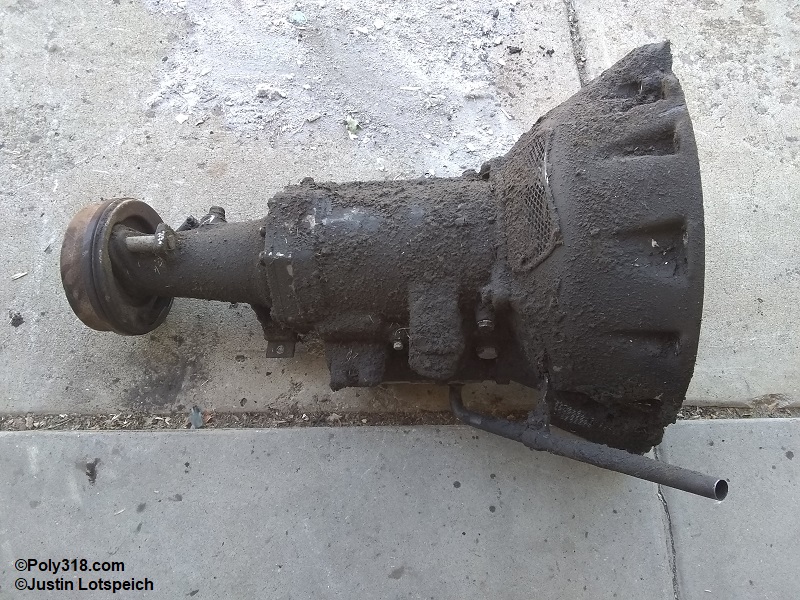

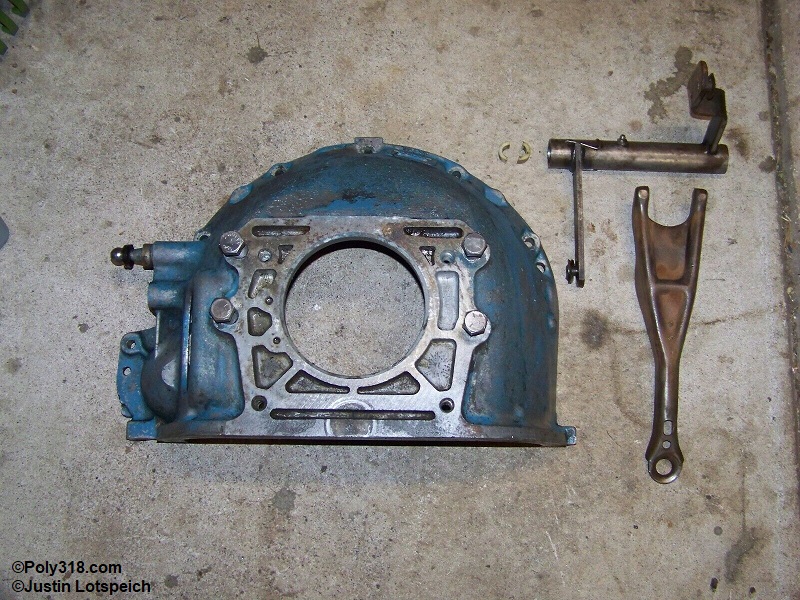

The first obstacle is that the 1956 – 1961 blocks share the same bellhousing bolt pattern and alignment dowel configuration as the Gen I hemi and hemi-block polys (except the 1951 – 1953 Chrysler 331 “extended block”) that is different from 1962 onward A/LA/Magnum. While the 1956 – 1961 A-block has a similar bellhousing bolt pattern to the LA, the alignment dowels are in different locations (Figures 2a – 2b above). Relocating the dowel pins or mating the LA bellhousing without them creates serious alignment issues. The only manual bellhousings and transmissions that connect to the 1956 – 1961 A-block are 1956 – 1961 cast iron Dodge truck, Hemi, and Hemi-block poly factory bellhousings, 1957 – 1959 dual-bolt-pattern from a 6-cylinder, and the matching three- or four-speed transmissions. The 1957 – 1961 Dodge truck bellhousings for the NP420 transmission are the most common of these options, but they are extremely bulky and heavy and may not fit all vehicles (Figure 5f). No A833 bellhousing—whether iron or aluminum—will bolt up to a pre-1962 block without modification or an adapter plate between the block and bellhousing (Figure 5g). To mate the LA bellhousing, an adapter must be either built or purchased (expensive) through early hemi specialists like Gary Stauffer’s Quality Engineered Components, Hot Heads, Wilcap, and TR Waters. For performance street/strip builds, I’ve used a scatter shield rather than an iron or aluminum bellhousing. Note that the iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite automatic transmissions used a separate bellhousing, but these are typically too long fore and aft to make the A833 input shaft pilot reach the flywheel bushing/bearing.

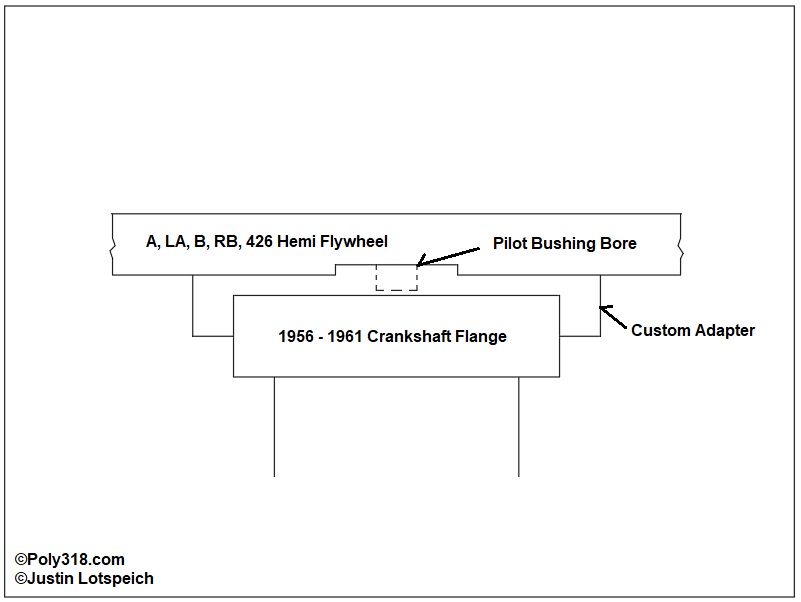

The second obstacle is that the 1956 – 1961 A-block automatic-transmission crankshafts have a 0.50″ longer rear flange and 8-bolt non-threaded pattern to mate to cast iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmissions (Figures 1a – 1c above). They also have a deep beveled end with nothing to hold a pilot bushing/bearing. A 6-bolt LA flywheel will not bolt up to the pre-1962 crank flange without an adapter that also incorporates a bore for a pilot bushing. This adapter must be sized to address the extra space created by the bellhousing adapter and to place the input shaft in the proper position fore and aft for clutch spine and input shaft pilot alignment. If one desires to install a 1957 – 1961 factory manual transmission setup, the 1957 – 1961 313, 318, or 326 manual transmission crankshaft must be used, which are rare compared to the automatic crankshafts. No aftermarket 1956 – 1961 crankshaft is available.

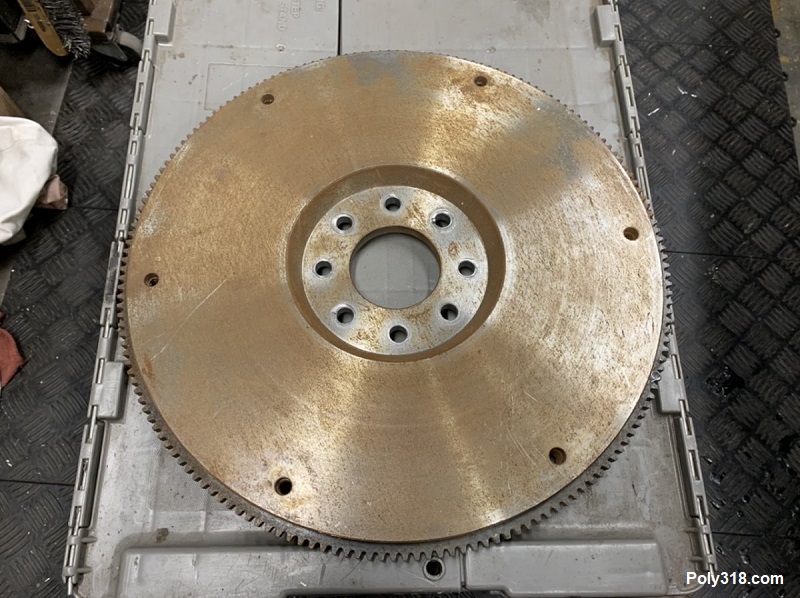

The third obstacle is the flywheel. The 1956 – 1961 A-block uses an 8-bolt pattern 146-tooth flywheel that registers on the outside of the crank flange (Figures 5h – 5i). Note that some vehicles, especially Dodge trucks, used a 172-tooth flywheel. Most A833 flywheels have a 6-bolt pattern, 130 teeth, 10.5” clutch used on most A, LA, B, and RB engines. (Note that the 1964 – 1968 LA273 uses a 9.5” 122 teeth flywheel that should be avoided). All 1962 onward flywheels register on the inside hub of the crankshaft. There are no factory or aftermarket 1962 onward flywheels that will work on a pre-1962 crankshaft without modification or an adapter similar to my drawing in Figure 5j. The most straightforward and likely most economical way to address the flywheel is to purchase a new reproduction late-426 Hemi flywheel such as the McLeod 464100 (Figure 5k), machine a crankshaft adapter that includes a well on one side to register on the crankshaft flange and hub on the other to register the Hemi flywheel, and press a pilot bearing into the flywheel (Figure 5l); the 1970 – 1971 426 Hemi uses an 8-hole pattern that matches the 1956 – 1961 cranksahft, 130-tooth, and 10.5” clutch flywheel that will work with the LA A833 bellhousings and starter motor. The holes in the crankshaft can be tapped 1/2″-20 for installing the Hemi flywheel. It is extremely dangerous to bolt a 1962 onward flywheel to the pre-1962 crankshaft without the adapter to register it. Relying on only the sloppy bolt tolerances is asking to brake the crankshaft at the rear and have flywheel shrapnel injury or kill the driver and others.

Another option that is likely more expensive than the 426 Hemi route is to have a machinist lathe down a 1956 – 1961 146-tooth flywheel, install a 130-tooth ring gear to use with an LA bellhousing, machine holes for the 10.5″ clutch, neutral balance the flywheel, and buy a bellhousing adapter plate to mate the LA bellhousing to the pre-1962 A-block; the adapter kit should include the appropriate crankshaft spacer, although a custom one may need to be built depending on the width needed and if the kit’s spacer doesn’t have a pilot bushing.

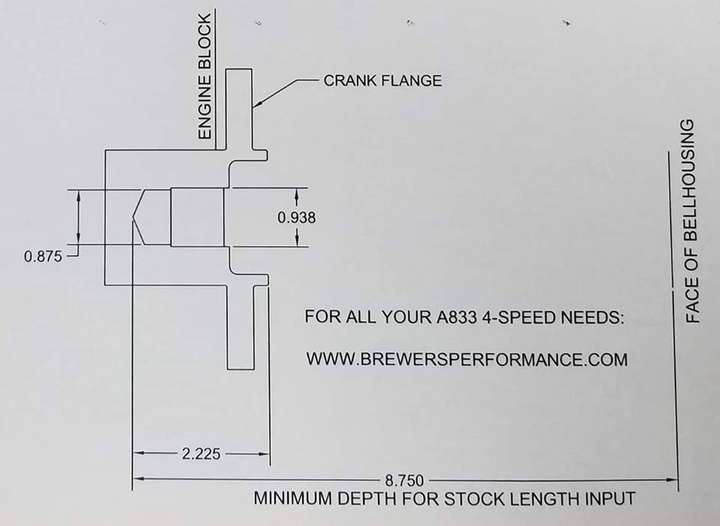

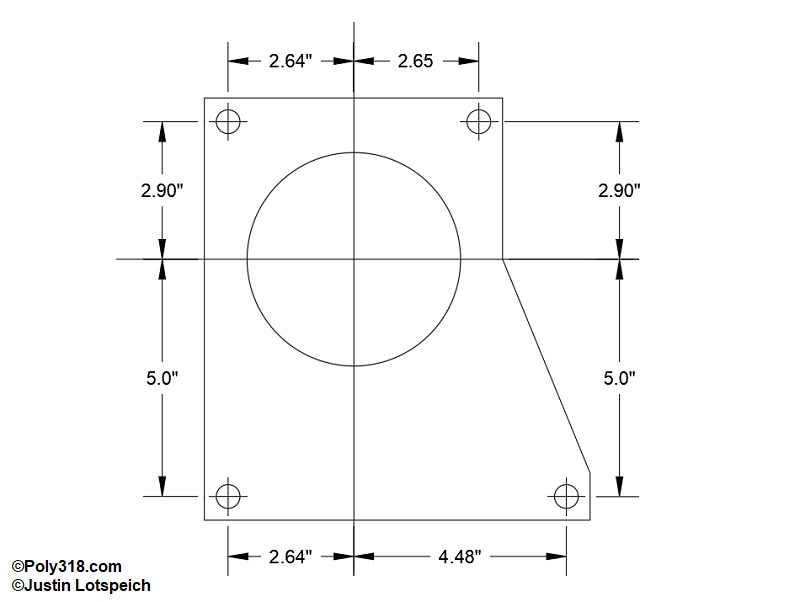

Another option is to use a factory 1957 – 1961 NP420 bellhousing, flywheel, starter, and build an adapter plate on the back of the bellhousing for the A833; a 1956 – 1961 aftermarket aluminum bellhousing might be an option too. I pulled measurements off an A833 bellhousing and drew up diagram Figure 5m for those interested in making an adapter plate out of 1/4″ – 3/8″ steel plate. The flywheel will need a custom spacer to bring it out the width of the custom adapter plate and to accept a pilot bushing, and the clutch and throw-out mechanism system will need addressing to work with both the A-block and A833 systems. Hydraulic throw-out bearings are handy in these situations.

Yet another option similar to the last option is to use a 1969 – 1980 Dodge heavy duty truck bellhousing 3497270 or 1981 – 1987 4202507 and starter motor made for the NP435 transmission that used a 6-bolt 143-tooth flywheel (Figure 5n). Using this bellhousing on a 1956 – 1961 A-block requires an engine-bellhousing adapter plate, crankshaft spacer with pilot bushing, and a custom bellhousing-transmission adapter plate to go from the NP435 bolt pattern to the A833 bolt pattern. The benefit of this setup is that you can use the factory 1956 – 1961 8-bolt 146-tooth flywheel since the 143-tooth starter motor will work with some clearancing by elongating its mounting holes. There is a B/RB bellhousing that uses a dual NP435/A833 bolt pattern for the 143-tooth flywheel casting 3893728, but no LA bellhousing with the dual pattern seems to exist from my understanding and after scouring parts manuals; if someone knows of this bellhousing for an LA, please email me so I may provide that information here.

With all the adaptation and modification needed to mate an A833 to a 1956 – 1961 A-block, it is especially critical to measure and adjust crankshaft-to-input shaft alignment once the bellhousing and all adapters/spacers are mocked up onto the block, which I detail below. Misalignment over 0.007″ can result in premature bearing/bushing wear at best and a catastrophic, potentially deadly broken crank, input shaft, and/or flywheel/clutch at worst.

A833 Gear Ratios:

The list below details the typical gear ratios for the different A833 versions, and these gear ratios should be considered when designing the entire vehicle system from engine torque output and rpm to rear tire height. Note that many of the pre-1974 ratios are “close”, while the overdrive ratios are “wide,” and gearing can be changed depending on the transmission. I say these ratios are “typical” because a few oddball factory configurations used different ratios than what I have listed here.

A833 Gear Ratios (typical): 1st 2nd 3rd 4th

23 Spline 1966 – 1970: 2.65 1.93 1.39 1.00

23 Spline 1971 – 1974: 2.44 1.77 1.34 1.00

23 Spline Slant 6: 3.09 1.92 1.40 1.00

23 Spline 273 (1964 – 1965): 3.09 1.92 1.40 1.00

23 Spline 318 (1974 – 1975): 3.09 1.92 1.40 1.00

18 Spline Hemi/Hi-Po 440: 2.66 1.91 1.39 1.00

18 Spline Race T/A (1971 – 1974): 2.47 1.77 1.34 1.00

A833 Overdrive 1975 onward: 3.09 1.67 1.00 .073 or 0.71

A833 Input Shaft and Crankshaft Alignment:

If I were forced to guess, I’d say 95% of people who swap transmissions from TorqueFlites to A833 or swap in a bellhousing, transmission, and other parts from multiple donors never check the crankshaft-to-input-shaft alignment. It seems logical that if a 1975 bellhousing fit on an LA318, it should just as easily fit on a 1968 LA318 or 1965 A318, but that assumption is deceiving. The jury is still out, but the common belief is that the factory mounted the bellhousing onto the block and then finished machining the bearing retainer hole in the bellhousing using a machine indexed to the crankshaft centerline. To me, this is a logical way the factory would have gone about the task, but for those of us mixing parts, we don’t have that luxury. We may slap that 1975 LA318 bellhousing onto our 1965 A318 and drive down the road, but the configuration could be outside the 0.007″ maximum runout allowed by the factory.

It is easiest to check the alignment with the engine removed from the vehicle. Bolt up the bellhousing torquing all the bolts appropriately, and jig up a dial indicator magnetic base on the crankshaft hub in a way that the gauge plunger contacts the inside of the bellhousing’s bearing retainer hole. Spin the crankshaft slowly by hand while monitoring the gauge. If the largest runout is at or below the factory maximum of 0.007”, the alignment passes factory tolerance. If the runout is over 0.007”. If the bellhousing is not within tolerance, the factory dowels need to be removed and offset dowels used, which can be sourced through Brewer’s Performance. Once the bellhousing is aligned within spec, use a “V” letter die as an arrow to mark the engine block and bellhousing in two different locations (I use one set of marks at the top and another set at one side) for proper alignment during final assembly.

New Venture NV3500, NV3500HD, and NV4500 in a 1962 – 1967 Poly 313, 318 A-block

The New Venture Gear NV3500 and heavy duty NV3500HD 5-speed manual transmissions are becoming popular swaps into mild LA engines and can be used with 1962 – 1966 A-blocks (Figure 6). They have an integral bellhousing that aligns with and bolts up to 1962 onward A/LA blocks except for the lower left bolt hole, which will not impact the bellhousing’s integrity. The NV3500 can be found in 1993 – 2001 Dodge Ram pickups with Magnum 318s, and the NV3500HD can be found in 1994 – 2004 Dodge Dakotas with Magnum 318s. GM also used the NV3500 with a different bellhousing, but I focus on the Mopar version since they bolt to the 1962 onward A and LA block. The NV3500 and NV3500HD are well suited for most mild and stock street applications, although they have a wide gear ratio starting with a 4.01:1 first to a 2.32:1 second. Keep in mind that they are hydraulic clutch systems, so plan on using the donor truck’s flywheel, clutch, throw-out bearing, slave cylinder, clutch master cylinder, etc. The transmission swap also requires using a Denso starter (I discuss starter options in another article). The Magnum 318 is internally balanced just like the A-block, so the flywheel is neutral balanced and will not cause balance issues with the A-block; it also bolts up to the 1962+ 6-bolt crankshaft.

The NV4500 is another option for A-blocks that will see towing and/or off roading. It has a separate bellhousing. The Mopar NV4500 usually came behind externally balanced Magnum 360s, so the flywheel is weighted and will not work on internally balanced A-blocks without neutral balancing it first; a Magnum 318 flywheel should be used with the NV4500. The NV4500 also has a wide ratio with a very low first gear of 5.61 that jumps to a second gear of 3.44. Of note, the 1993 – 1994 Chevrolet and GMC NV4500 has a monster of torque first gear of 6.34:1 for those interested, but the bellhousing configuration and input shaft length differ from the Mopar version and will need addressing. The Mopar NV4500 can be found in 1994 – 2004 Dakota, 1994 – 2001 Ram 1500, and 1994 – 1995 Ram 2500 Light Duty. As with the NV3500, plan on using the donor truck’s hydraulic clutch system.