Poly 318 History and Debunking Myths

Introduction of the Poly A-block Engine

This page is dedicated to going through the historical changes to the A-block and the common myths and misconceptions that the poly engine has picked up over the decades. The 1950s came with the most confusing engine decade for the Mopar divisions but saw technological advancements that would become mainstays of the muscle-car era onward. I started this page with the historical context that led to the development and manufacture ring of our beloved A-block V8, but the content around the new engine and the two factories that produced it became so voluminous that I dedicated a page to the development and factories that I highly recommend readers review before reading this page to provide a robust understanding of the A-block and the many engineers, mechanics, and assembly people who brought us the engine.

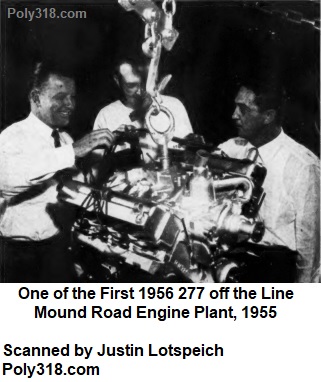

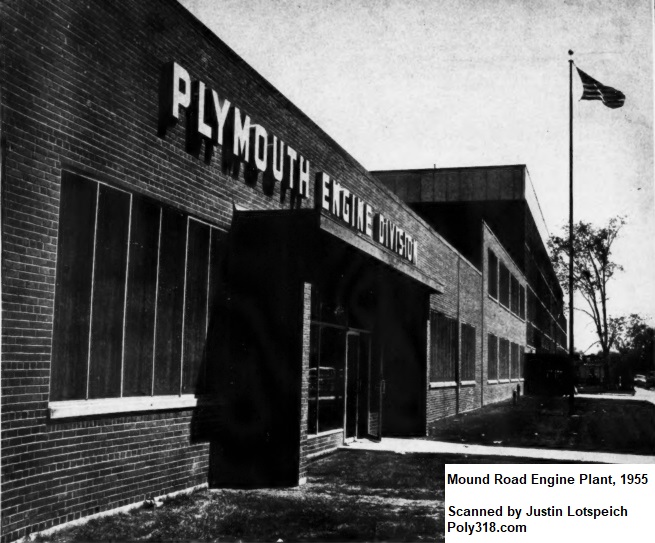

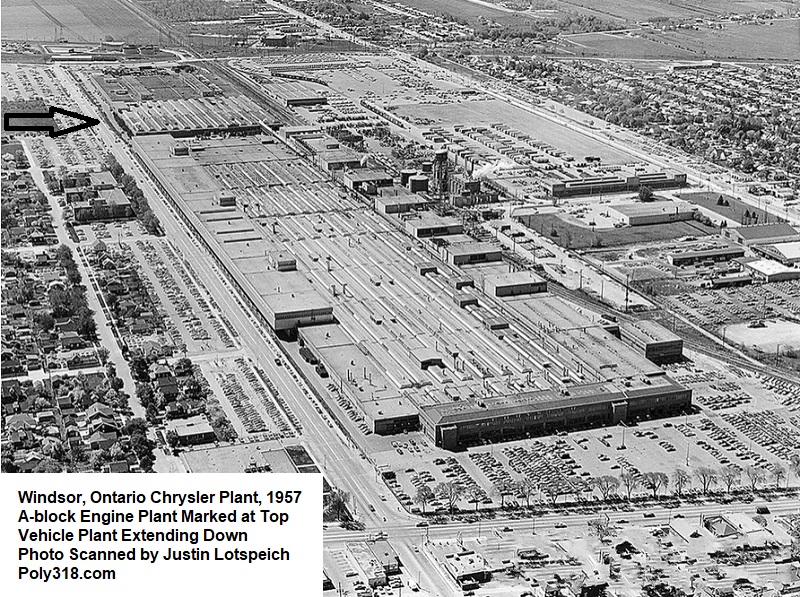

While the engine-plant page starts a little earlier, for the purpose of this page our journey starts in mid-1955 when the first Plymouth A-block 277 rolled off the assembly line (Figure 1a) at the “Qualimatic” Mound Road Engine Plant in Detroit, Michigan (Figure 1b – 1c) and the first A-block 303 was finished at the Windsor Engine Plant, Ontario, Canada (Figure 1d). The Mound Road Engine Plant was revolutionary in the automotive industry with processes and methods that became standard across the industry, and the A-block engine was the catalyst. The Mound Road and Windsor engine plants would crank out all the A-blocks from 1956 – 1967 that we admire.

Mound Road Engine Plant, 1955

Photo of Expanded Campus, 1957

Combustion Chamber Design

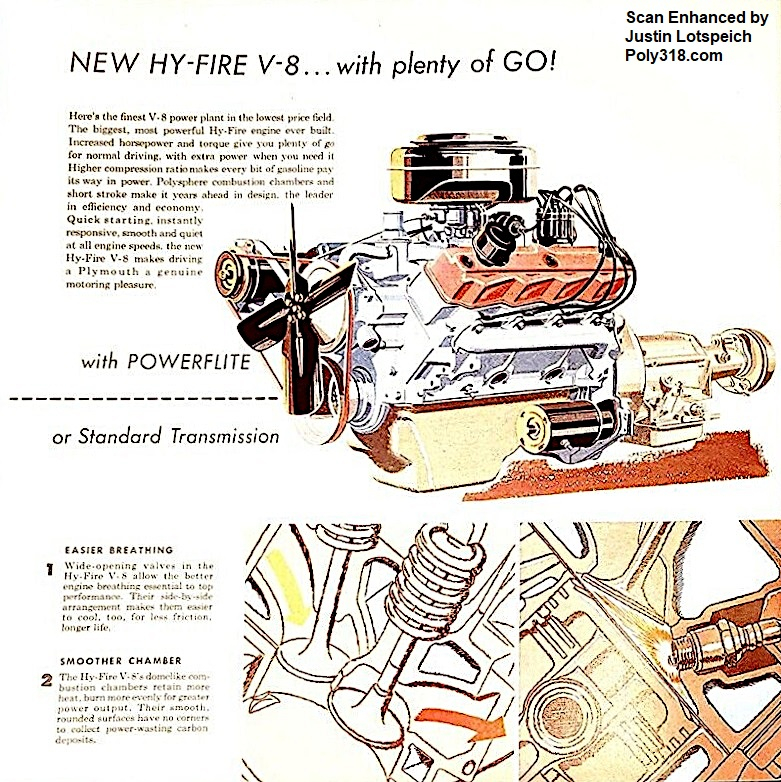

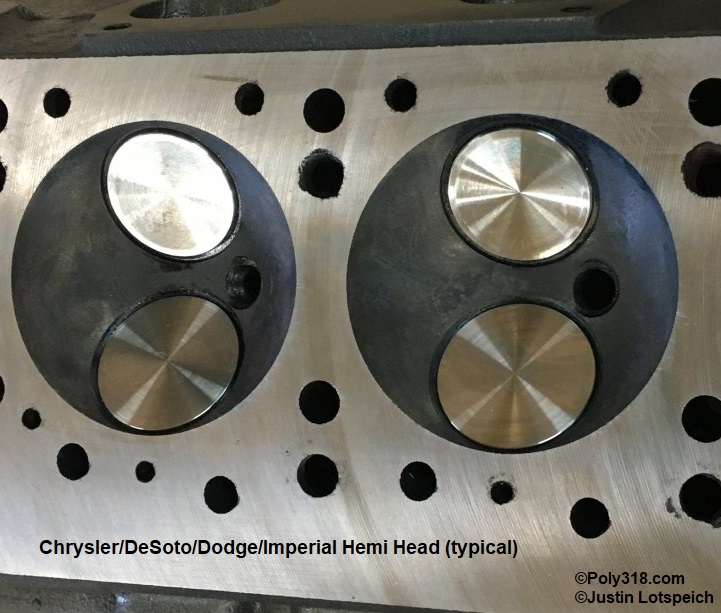

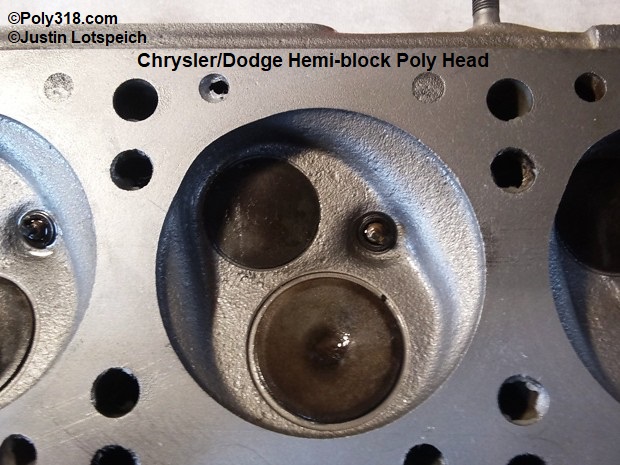

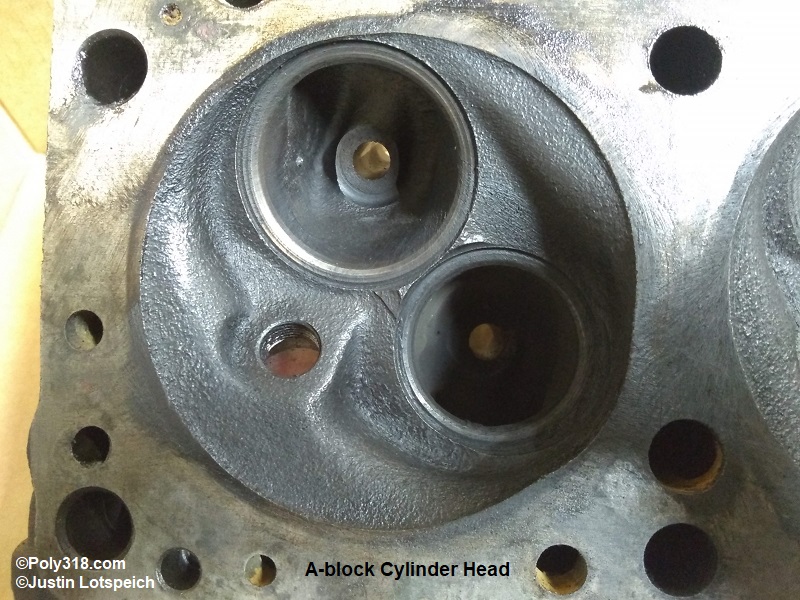

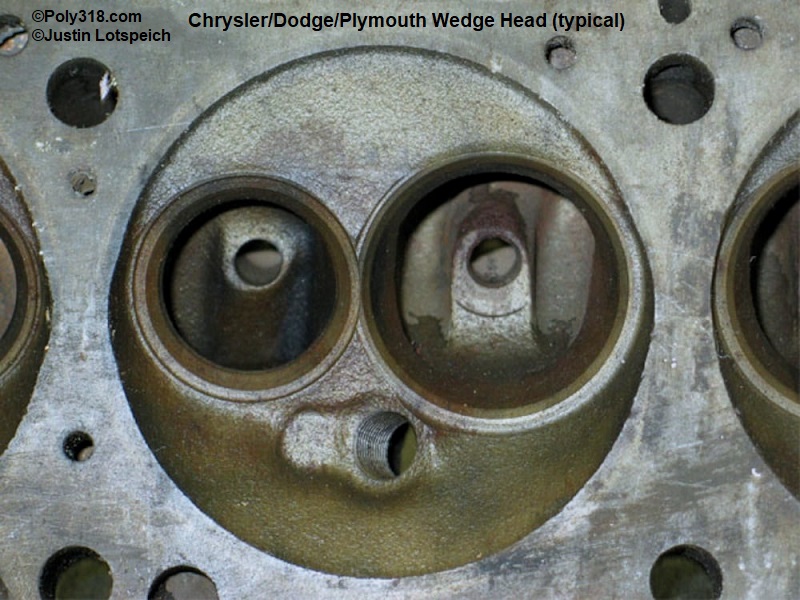

Before leaping into the A-block changes throughout the years, a lot of people might ask what a “polyspherical” engine is and how it differs from a “Hemi” and a “wedge.” The three terms refer to the combustion chamber and valve configuration and for the Chrysler Corporation developed in the 1950s. For 1951, Chrysler Corp. introduced a V8 with hemispherical combustion chambers (Figure 2a) whose intake and exhaust valves are opposite each other. They designed another head for 1955 that bolted to the Hemi shortblocks (Figure 2b) whose intake and exhaust valves were diagonal each other, canted, and positioned down in a stepped well rather than a sphere like the Hemi. Plymouth began referring to this design as a “polyspherical” chamber as early as 1955 according to an internal factory article. While Plymouth, Dodge, and Chrysler did not advertise the A-block as a “polyspherical” chamber in the 1950s from the brochures I’ve found, by 1959 the term began showing up in both domestic and export brochures. For the 1956 model year, Plymouth designed a new engine family drawing on the Chrysler and Dodge polyspherical combustion chamber with diagonal canted valves that they named the A-block (Figure 2c). For the 1958 model year, Chrysler Corp. aligned itself more with GM and Ford cylinder head designs by introducing the wedge-shaped combustion chamber on the new B-block engine family whose intake and exhaust valves are inline in a wedge-shaped chamber (Figure 2d). This change was made for multiple reasons I don’t cover here, but the B-block engine design team made up of members who helped design the A-block used many lessons learned from the A-block when designing the B. Now that the terminology is set, onto focusing on the A-block’s history.

Plymouth Poly A-block Engine Historical Timeline

1956 Plymouth Poly Engine: The New Engine Family Smashing Speed Records

The Plymouth Division introduced the new A-block 277 for 1956 USA models and some export Plymouth and Dodge models and an overbored 2-barrel 303 for export Dodge Custom Royal and 4-barrel 303 in Chrysler Windsor largely sold in Canada, Australia, and Britain. The domestic 1956 Fury came standard with the 303, 9.25:1 compression pistons, hotter cam, stiffer valve springs, dual-point distributor with performance curve, single four-barrel WCFB carburetor, and dual high-flow exhaust. The A-block was not available in 1956 Chrysler, DeSoto, Dodge, or Imperial vehicles. The A-block combustion chamber design borrowed from the Chrysler and Dodge Hemi-block poly engines but was a completely new and advanced design with multiple features that would survive in Mopar engines into the 21st century.

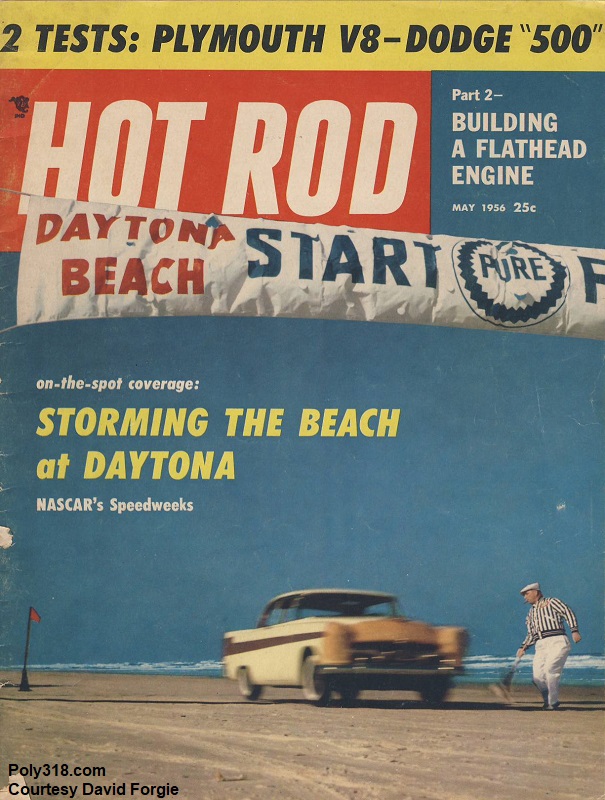

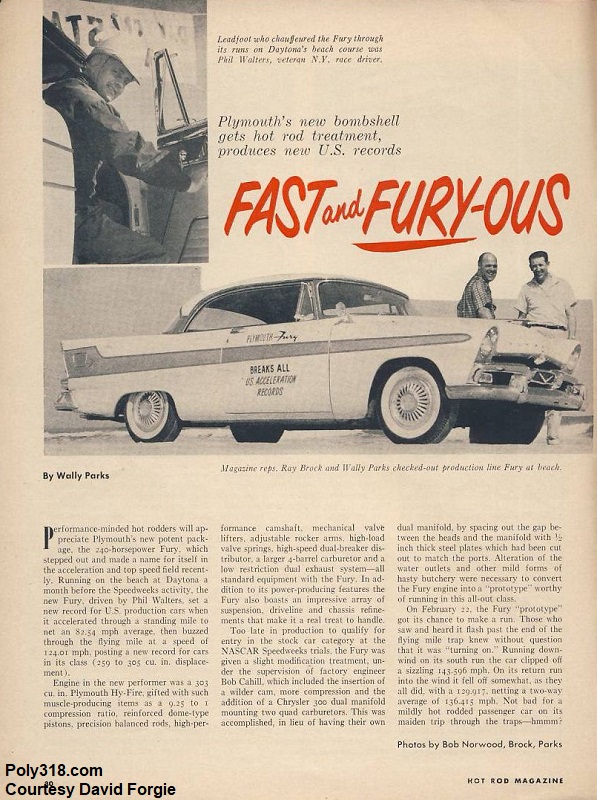

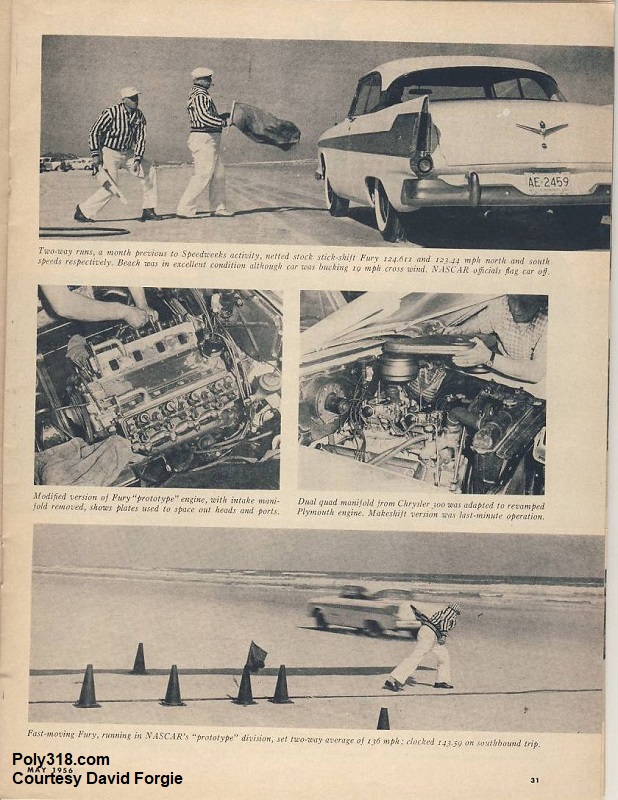

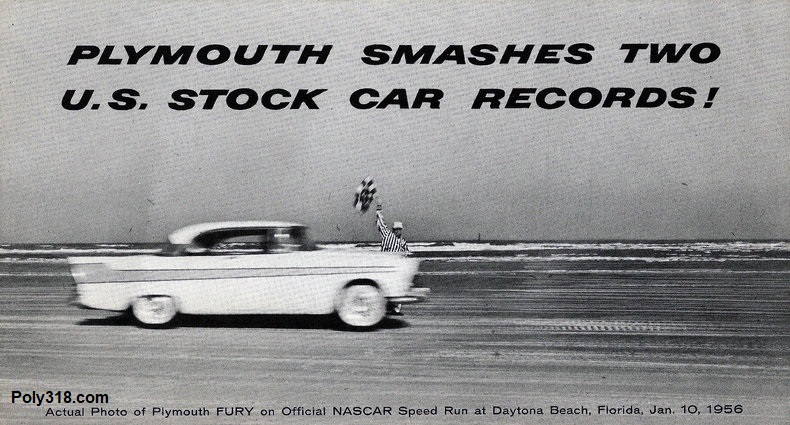

Plymouth pushed the performance of its new A-block and offered factory performance parts including an aluminum dual-quad intake manifold (see the intake manifold page). In January 1956, Plymouth under the supervision of engineer Bob Cahill entered a modified 1956 Fury in the “all-out” class of the 1956 NASCAR Speed Run at Daytona Beach, driven by Phil Walters. The car’s 303 was modified with higher compression pistons (compression ratio unknown), hotter cam than the standard Fury, and a Hemi dual-WCFB intake manifold from a Chrysler 300 with custom adapters and lifter valley cover to make the intake work on the A-block. Why engineer Cahill used the Hemi intake manifold rather than the A-block aluminum dual-quad intake is unknown but was possibly due to the A-block intake manifold not being in production at the time of the test. The car set a new speed record for 259 – 305 c.i.d. domestic engine cars at 82.54 MPH on average in the standing mile and 124.01 MPH on average in the flying mile. It ran an all-out 143.596 MPH at its best with a tailwind and 19 MPH crosswind and 136.415 MPH with a headwind and 19 MPH crosswind. The test is detailed in both the may 1956 Hot Rod Magazine (Figures 3a – 3c) and in Plymouth advertisements (Figure 3d). I include vintage performance A-block photos at the bottom of this page.

For 1956, the A277 used the PowerFlite 2-speed automatic transmission.

1957 Poly Engine

1957 brought a lot of changes, so try and keep up: Plymouth was still the only division offering the A-block but began phasing out the 277 (domestic) and 303 (export). The 277 came standard in the 1957 Plaza. Plymouth revised the block for a larger bore of 3.91″ and increased the stroke to 3.31″ to make the 318 that came standard in USA Fury but was an option in all models according to period brochures. Plymouth Belvedere, Savoy, and Suburban models received a one-year oddball 301 built by using the new 318 block with the stockpile of 277 crankshafts.

Export vehicles either came with the remaining 303 engines or began receiving the new 313, which is an under-bored 318. The 303 came as the standard V8 in export Plymouth and Plymouth-body Dodge (Plodge) 118″ wheelbase cars. Canadian Dodge and Fargo trucks received their first A-block with the 303, while the Chrysler Windsor stopped using the A-block and went back to either the hemi or hemi-block poly.

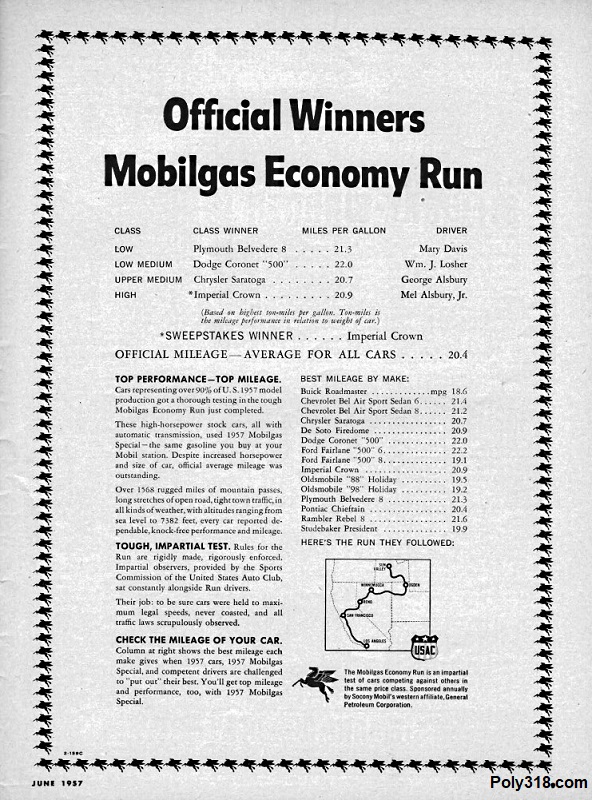

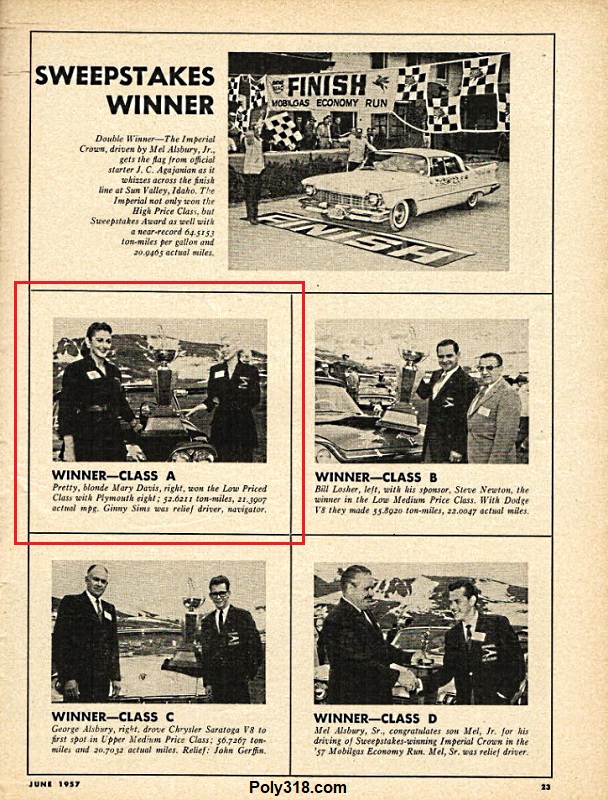

Plymouth began advertising the A-block to commuters focused on fuel economy after its first place finish in the “Low” model Class A at the 1957 Mobilgas Economy Run. Lead driver Mary Davis and relief driver and navigator Ginny Sims as early examples of women competing in automotive competitions (despite Figure 4b’s sexualization of them compared to how their male competitors are described) won their class in a 301 A-block and TorqueFlite A466 powered Plymouth Belvedere at 21.3 MPG average over the four-day 1,568 mile road course from Los Angeles, California to Sun Valley, Idaho (Figures 4a – 4b).

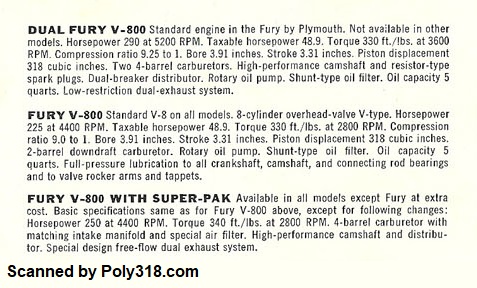

Plymouth, like Dodge, advertised their engine not only as a solid commuter and vacation option but as a factory performance race car (Figure 4c). The advertisement’s 1957 Fury grille has a “Westfield Timing Association” plaque, and the text brags about how “[o]n every big strip in the country, professional competition drivers are taking their hats off to new Plymouths powered by the new Fury V-800s.” Some people think the V-800 is the dual-quad carburetor 290 HP version of the 318 available as an option only in the Fury, but, in fact, all 1957 – 1958 318 engines were called “Fury V-800” in the domestic market. Export sales brochures did not use the Fury V-800 names in 1957. The 1957 – 1958 318 offered three different versions of the A-block: “Dual Fury V-800,” “Fury V-800 Super-Pak,” and “Fury V-800,” as Figure 4d from a brochure shows and I break down. Export 313 don’t appear to have ever used these names.

- Dual Fury V-800: The only true factory “high-performance” A-block ever offered standard and available only in 1957 and 1958 Fury models. It boasted a cast-iron dual-quad intake manifold with Carter WCFB carburetors, a hotter cam, higher compression of 9.25:1, high-flow dual exhaust, dual-point distributor, and resistor spark plugs. It put out an advertised 290 HP at 5,200 RPM and 330 ft./lbs. torque at 3,600 RPM.

- Fury V-800 Super-Pak: An optional engine for all 1957 – 1958 models except the Fury with cast-iron single Carter WCFB four-barrel intake manifold, 9:1 compression ratio, hotter cam, high-flow dual exhaust, and performance-curve distributor. It put out an advertised 250 HP at 4,400 RPM and 340 ft./lbs. torque at 2,800 RPM.

- Fury V-800: The standard engine for all 1957 – 1958 models except the Fury (but optional in the Fury) that would go on to be the standard V8 for most Plymouth, Dodge, and Chrysler cars and trucks through 1967. The engine won the Mobilgas Economy Run championship, which Plymouth advertised heavily to commuters and vacationers. It came with a cast-iron single 2-barrel intake manifold and 9:1 compression ratio. It put out an advertised 225 HP at 4,400 RPM and 330 ft./lbs. torque at 2,800 RPM.

1957 was also the first year that Plymouth Fury, Belvedere, Sport Suburbans had the optional cast-iron TorqueFlite A466 3-speed automatic transmission, while the Savoy and Plaza continued using the 2-speed PowerFlite.

Figure 4b: 1957 Mobilgas Economy Run Results, Plymouth 301 Winners in “Class A”

1958 Poly Engine

The 277, 301, and 303 were discontinued in place of the 318 as the standard engine in domestic Plymouths. The same V-800 engine packages and specifications described under 1957 applied to 1958. Plymouth continued advertising the Fury V-800 as the champion of the Mobilgas Economy Run.

Export Plymouths continued receiving the 313, and Dodge Mayfair, Regent, Crusader, and Suburban models received the 313 as the standard V8. Canadian Dodge and Fargo trucks continued offering the 313. Export Chrysler did not offer the A-block. Export brochures continued to not use the Fury V-800 names.

Of note, content floating around online suggests that Chrysler began using the A-block in 1958, but all the USA and export sales brochures I’ve found do not include the A-block as an option.

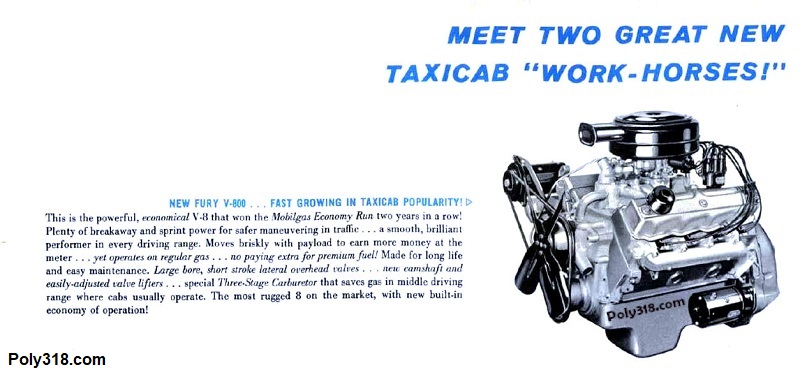

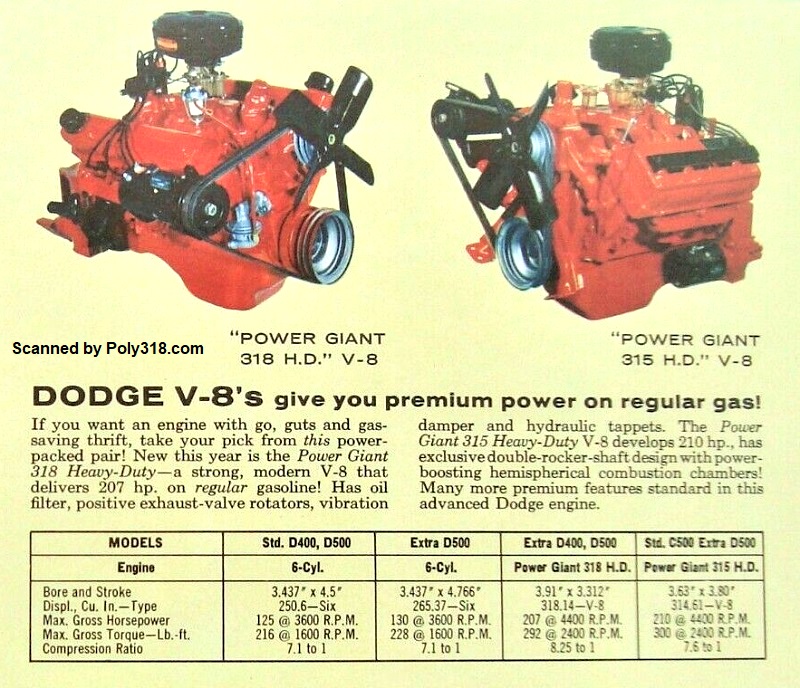

1959 Poly Engine: First use of “Polyspherical” Terminology

Plymouth continued using the 318 in domestic cars and the 313 in exports. Performance increased very slightly (see the specifications page for full details). The names “Fury V-800” and “Fury V-800 Super-pak” were used for domestic vehicles, although the “Dual Fury V-800” was discontinued. One explanation for Plymouth moving away from the A-block as a factory performance engine is the release of the B361 “Golden Commando 395” engine in the Fury that Chrysler Corporation marketed heavily as the ultimate performance engine. Plymouth continued advertising the Fury V-800 as the champion of the Mobilgas Economy Run (Figures 5a – 5b). Dodge began offering the 318 in trucks advertised in the domestic market as a “Power Giant 318 Heavy Duty” and using 318.14 c.i.d. in the specifications (Figure 5b).

Dodge car engineers overbored the 318 to 325 as the standard V8 for the domestic Coronet, which they advertised as a 326 to differentiate the A-block engine from their 325 Hemi and Hemi-block poly engines previously used. The Dodge 326 is a one-year engine that used a hydraulic flat-tappet camshaft and lifters and nonadjustable rocker arms, whereas the standard Plymouth 318 and 313 used mechanical flat-tappet camshaft, lifters, and adjustable rocker arms. Chrysler did not offer the A-block.

Export Plymouth and Dodge continued offering the 313, while Chrysler did not. Export Dodge trucks called the engine a “313” with “Power Dome polyspherical combustion chamber.” This is the first time in factory brochures/literature that I have seen the term “polysherical” used in reference to the A-block, although the engine design team was referring to it internally as such in 1956.

Chrysler Corporation’s Industrial Engine Division (under the Special Products Group) introduced the first factory A318 industrial engine in the “H-Series” advertised at 190 HP. The models include the H318, HC318, HB318, and HT318. See the marine and industrial engine page for more details about the specifications for different models within the H-Series.

Chrysler Corporation’s Marine Engine Division (under the Special Products Group) introduced the first marine A318 in the “M-Series” with the “Chrysler Sea V” advertised at 177 HP with its unique valve-cover decal and “Sea-V Blue” metallic paint (see the engine color’s page for a full list and photos of all the factory A-block colors). See the marine and industrial engine page for more details about the different models within the M-Series.

1960 Poly Engine: The Year of Standardizing

For the 1960 model year, Chrysler Corp. simplified their engine options and made the 318 the standard small-block V8 engine for Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge for domestic cars and trucks and continued the 313 for export models. Plymouth and Chrysler continued calling the 318 “Fury V-800” and “Fury V-800 with Super-pak.” Dodge continued using the “Red Ram” for the domestic car 318, which came standard on at least Pioneer and Seneca wagon models. Dodge domestic heavy truck brochures call the engine a “Power Giant 318 with Power Dome combustion chambers.” Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge called the export “313 V8.”

Chrysler Corp. continued offering the “Chrysler Sea V” marine engine. While I continue to search for factory evidence to pinpoint the exact release year, somewhere around 1960 Chrysler’s Marine Engine Division introduced the “Chrysler M318A” 318 with its unique valve-cover decal.

1961 Poly Engine

The 318 remained the standard small-block for Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge for domestic cars and trucks and the A313 for export models. I found two different Plymouth brochures that use different names for the 318 packages. For domestic, the “Fury V-800” continued. One brochure calls the four-barrel package “Fury V-800 Super-pak” like years before, but another brochure calls it the “Super Fury V-800.” Dodge appears to drop the “Red Ram” and call it the “Standard 318 V8.” Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge called the export “313 V8.”

Though not common, Dodge began offering the “Semi-Premium” 318 option in light trucks and denoted by a 318-2 or superscript 2 stamped on the left front of the block. They began offering the “Full-premium” 318 as the standard engine package in heavy trucks including D400, D500, D600, W300, and W500 denoted by the 318-3 or superscript 3 stamped on the left front of the block. The “Semi-premium” and “Full-premium” packages were available in Dodge trucks through 1967. For details about the different components used in the “Standard,” “Semi-premium,” and “Full-premium” engine packages, see the engine identification page.

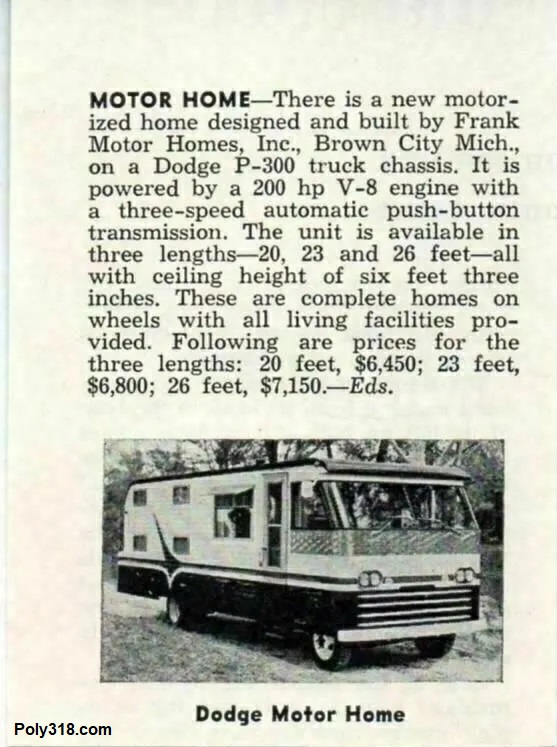

Dodge struck a collaboration partnership with Frank Industries and began selling the Dodge Frank Motor Home based off a modified heavy Dodge truck chassis and A318 (Figure 5d). Period advertisements call the motorhomes “Dodge Motor Home.” This partnership and Dodge-branded motorhomes with the A318 would continue through 1964.

1962 Poly Engine: The Redesign

In 1962, the domestic A318 and export A313 saw major changes to the block and components that would last through the end of A-block production and in many ways continue into the LA-block and then the Magnum engines. Of particular importance for those interested in running an A-block, 1956 – 1961 A-blocks use the same bellhousing bolt pattern and alignment dowel position and 8-bolt crankshaft flange pattern as most of the 1950’s Hemis and Hemi-block polys offered by Chrysler, Dodge, and Hemis offered by DeSoto. The crankshaft flange is 1/2″ longer on the first-generation A-blocks to mate to the cast-iron PowerFlite and TorqueFlite A466 transmissions that use a spacer plate between the block and bellhousing. Therefore, the 1956 – 1961 A-blocks will not accept a 1962 onward aluminum TorqueFlite transmission or a 1962 onward standard transmission bellhousing without an aftermarket adapter (see the crankshaft and transmissions page for more details and photos on transmission options and the block and crank year differences). The redesigned 1962 A-block bellhousing bolt pattern and alignment dowel position would go on to become the LA and Magnum patterns. Chrysler Corp. engineers would also use many of the internal and external components of the 1962 redesigned A-block when they designed the LA family with the 273 released in 1964 followed by the LA 318, 340, and 360, which I detail in the parts interchange section. Note that the changes I cover here are not the only changes, which the parts interchange section covers in depth.

The “Fury-V800” and “Fury V-800 Super-pake” names were continued on domestic Plymouth and Chrysler brochures, but the oddball “Super Fury V-800” from one 1961 brochure does not appear on the 1962 brochures I’ve found. Dodge continued using the name “Standard 318 V8” for domestic vehicles. Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge called the export “313 V8.”

1962 was the last year for the four-barrel “Fury V-800 Super-pak” in vehicles, although the four-barrel was offered in marine engines through the end of marine A-block production in 1967.

Dodge Motor Homes continued offering the A318.

1962 was the first year the A318 received the newly designed aluminum TorqueFlite A727 3-speed automatic transmission. The transmission was also an option in 1962 Dodge trucks, which Dodge renamed “LoadFlite” from 1962 – 1965 before the name was dropped to use TorqueFlite like the rest of Chrysler Corp. vehicles. From my research and after compiling an extensive identification database for the PowerFlite and TorqueFlite transmissions, the A318 never received the TorqueFlite A904 3-speed automatic transmission from the factory.

Chrysler’s Marine Division began phasing out the “Chrysler Sea V” A318 and stopped using the “Chrysler M318A” name and valve cover decals. Instead, they introduced the M-series “Fury” line of marine engines that would run through end of A-block production. The number in the model represents the advertised HP rating, and factory parts and service manuals use an “M” code for each engine. More details are on the marine and industrial engine page.” Of note, the “Fury 235″ M318D” was not yet released.

- “Fury 190” M318A

- “Fury 195” M318B

- “Fury 210” M318C

1963 Poly Engine

The two-barrel “Fury V-800” became the remaining induction option standard in many Plymouth and Chrysler vehicles, and Dodge continued using the “Standard 318 V8” name for domestic vehicles. Plymouth, Chrysler, and Dodge called the export “313 V8.”

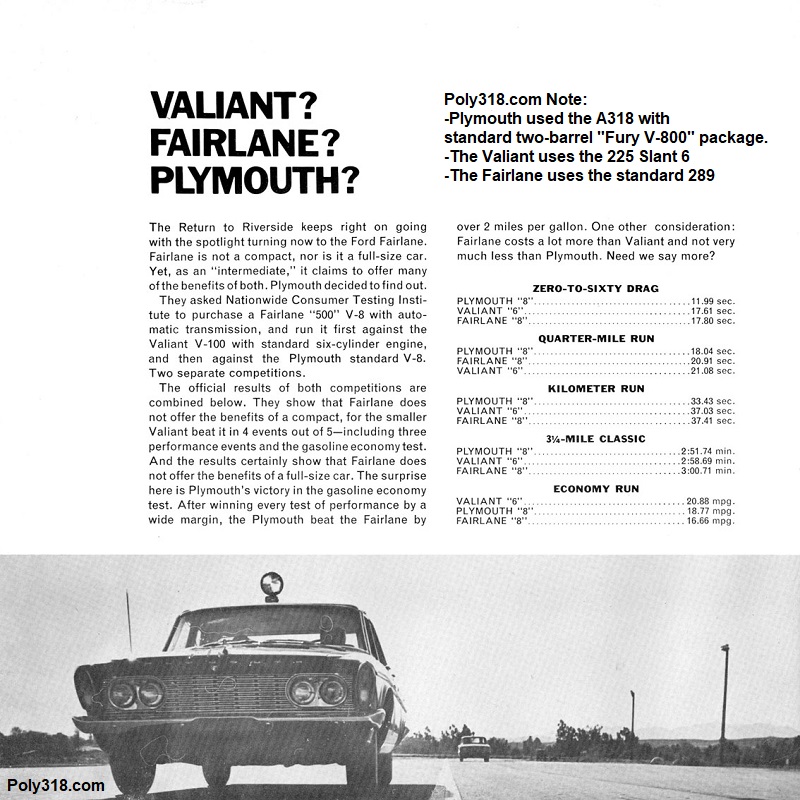

Chrysler released the results of an interesting performance and economy head-to-head test conducted at Riverside Raceway, California called “Return to Riverside” between 6-cylinder Plymouth Valiant, Chevrolet Corvair, Chevrolet Chevy II (Nova), Ford Falcon, Plymouth Fury with an A318, and a Ford Fairlane with a 289. The results show the Fury with a “Fury V-800” (2-barrel) A318 won the 1/4 mile against the Fairlane 289 by about 3 seconds, although still slow at 18.04 seconds, and beat the Fairlane in a 3-1/3 road course by half a second (Figure 6a). I have the full write-up PDF for free download on the manuals page.

Dodge Motor Homes continued offering the A318.

As a side note just to track the history, Chrysler Corporation’s Special Products Group that since 1959 was in charge of developing and selling A318 industrial and marine engines split into two distinct divisions: the “Industrial Products Division” and the “Marine Division.” This change didn’t impact the A-block since it had always been advertised and marketed on the engine name plate as the “Industrial Engine Division” or as the “Marine Engine Division.”

While I have not been able to find factory evidence to pinpoint the release year, sometime around 1963 the Marine Engine Division discontinued the “Fury 190” 318 marine model and added the “Fury 235” M318D to the lineup of “Fury 195” and “Fury 210.” My 1962 marine factory service manual (free for download along with other manuals) does not include the “Fury 235,” but by 1964 the model appears in advertisements.

1964 Poly Engine

Plymouth and Chrysler continued the “Fury V-800” name and Dodge the “Standard 318 V8” for domestic vehicles.

The export A313 in Plymouth and Chrysler started using the name “Fury V-800,” which I have not found on brochures prior to 1964. Dodge continued using “Standard 313 V8” for export vehicles.

Dodge Motor Homes continued using the A318, which was the last year of the Dodge-branded motorhome with an A318 as Dodge and Frank Industries transitioned the motorhome production to Travelers Company (Travco).

Of importance in the A-block’s saga, Chrysler Corporation introduced the first LA engine, the 273, under the design leadership of Willem Weertman who coincidentally was the first junior resident engineer at Plymouth’s Mound Road Engine Plant in 1954 and saw the first A277 roll off the assembly line, although from articles written by the A-block design team Willem did not play a significant roll in the A-block’s development since he was a junior resident amongst a team of seasoned engineers. In an interview years later, Weertman provided details about the move away from the A-block into the “Light A” (LA) block. He said, “The biggest difference between the LA and A engines is really the valve arrangement. We went from a skew valve type of arrangement on the A engine, which had the exhaust valve parallel to the bore and the intake valve tipped toward the intake manifold giving what has been described as a polyspherical chamber. . . . When it came to the LA engine we made all the valves tipped to the intake manifold and inline, as viewed from the front of the engine, giving it a wedge-shaped combustion chamber. The reason we went to such a change, which triggered totally new cylinder heads and manifolds for the engine, was that the engine was designed to go into the Valiant car. The Valiant car was originally not designed to take a V-8 engine, so we were really limited in every which way about getting the engine in place, and the older A engine was simply far too wide at the cylinder heads in order to go into the car. So we put the wedge cylinder heads on top of the A engine and that was what we needed to do in order to get that engine into the Valiant. In the process we also wanted to take a lot of weight out because the Valiant [engineers] wanted to have engines much lighter than what a conventional A engine would be. So we took as much as we could out of the cylinder heads and the intake manifold and the cylinder block which is the largest and heaviest piece of an engine. That triggered a new casting process for the cylinder block that allowed us to make all the walls thinner. . . .”

Willem Weertman, one of the men who helped usher in the A-block starting in 1954 at the Mound Road Engine Plant, ironically led the design team of the LA that would kill the A-block.

1965 Poly Engine: End of the 313

Chrysler Corp. retired the A313 in its export cars and trucks and replaced it with the A318 used in the domestic market. There are examples of the A313 making its way into some 1965 export cars, though these cases are extremely rare.

The long-running “Fury V-800” name was dropped in both domestic and export brochures and replaced with “Standard 318 V8.”

Ray Frank of Frank Industries moved motorhome production to Travelers Company, better known as Travco, and contracted with Dodge to continue supplying the A318 and heavy truck chassis for Travco motorhomes.

1966 Poly Engine: Domestic Farewell

With the popularity of the LA273, particularly the hopped up 273 Super Commando with its factory Edelbrock aluminum intake manifold and Holley carburetor, plans to release the LA318 and LA340 for the 1967 model year, and a desire to simplify engine production, Chrysler Corp. chose 1966 as the last year the A318 was offered in Plymouth, Dodge, and Chrysler domestic cars and trucks, which they continued calling the “Standard 318 V8.”

Travco motorhomes offered the A318.

1967 Poly Engine: End of the Road

1967 heard the dead bell toll for the A-block in export markets, which continued using the name “Standard 318 V8” not to be confused with the LA318. Chrysler Corp. used up the last of its A318 stock–aside from saving a cache of replacement parts–in its export cars and trucks with most of them sold in Canada. Some of these Canadian-built cars and trucks made their way into the USA market but are still considered export vehicles.

Travco motorhomes continued using the A318 in some models for the final year.

The Industrial Products Division and the Marine Division stopped advertising the A318 around this time in favor of the new LA318, although there are reports of new-old-stock A318 engines making their way into industrial and marine applications as late as the early 1970s; these instances don’t appear to have been pushed by Chrysler Corp., however, and were likely through private distributors and private manufacturers using up their stock or making use of discounted new-old-stock engines.

Debunking Garage and Online Myths and Confusion

Now that we have a handle on the A-block’s history, I want to address common misconceptions about the A-block that have survived through the years regardless of the facts.

Poly What? There Are Two Poly Engines?

Many people throw around the term “poly” as if there were only one type of Chrysler Corporation engine family with polyspherical heads. What we call the poly 277, 301, 303, 313, 318, and 326 is the A-block family and the first small block V8 Chrysler Corp designed. All A-blocks have polyspherical heads and a unique shortblock vastly dissimilar to any other Chrysler Corp engine up until 1964. The confusion stems from Chrysler Corp having multiple 1950’s V8s that use the early Hemi shortblock equipped with polyspherical heads including Dodge 241, 259, 270, 315, 325 and Chrysler 301, 331, 354. Note that before the A-block’s introduction in 1956, Plymouth cars used Dodge V8s, and DeSoto never offered a hemi-block polyspherical head engine or an A-block. These Dodge and Chrysler Hemi-block engines equipped with polyspherical heads are typically referred to as “polys” or “semi-Hemis” but are extremely different from the A-blocks with almost no parts interchangeable save for small parts like the thermostat housing. I find that using the “A-block” and “Hemi-block poly” distinctions clears up the “poly” confusion.

“Semi-Hemi” not even Semi-true

Yes, to the disappointment of anyone with an A-block wanting to ride the coattails of the famed early Hemi when describing his engine or slapping on an aftermarket “Semi-Hemi” valve cover or air cleaner decal, a poly A-block is not remotely a “semi-Hemi.” The semi-Hemi moniker came about in the 1950s among hot rodders and mechanics after Chrysler and Dodge for the 1955 model year designed a cylinder head with a single rocker-arm shaft configuration and polysherical combustion chambers that bolted onto the Hemi shortblock assemblies as a budget option for consumers over the more expensive Hemi head. The moniker “semi-Hemi” has nothing to do with the shape of the polysherical combustion chamber but with the fact that these engines are part Hemi in the shortblock. Completely opposite, the 1956 – 1967 poly A-block heads cannot be bolted onto a Hemi shortblock, nor can Hemi heads be bolted onto the A-block shortblock, so there is nothing semi-Hemi about the A-block just as there is nothing semi-A about the Hemi. The moniker sounds catchy and allows someone to utter the word Hemi, but only Chrysler and Dodge Hemi-block polyshperical-head engines are “semi-Hemi” according to how the term was originally used in the 1950s – 1960s.

A-blocks Are Cheap Engines

A misconception that is perpetuated online without evidence is that Plymouth designed the A-block engine as a cheap alternative to the Chrysler, DeSoto, and Dodge Hemi and Hemi-block poly V8s, but this assertion is not supported by historical documentation written by Plymouth executives and the very people who designed the A-block, production processes, and engine plant. In reality, rather than wanting a cheap engine, Plymouth spent the most money ever for the time on developing the A-block engine, the production processes, and the Qualimatic Mound Road Engine Plant to push engine design and manufacturing into a new technological era. Between 1954 and mid-1955, Chrysler Corporation spent a staggering $50 million on the A-block program, the equivalent of $544 million as of 2020—the most money ever spent on designing and producing an automotive engine at the time. The “cheap” myth in the same way as the “semi-Hemi” myth in fact confuses the A-block with the Hemi-block polyspherical head engines Chrysler and Dodge offered alongside their Hemis. These Chrysler and Dodge poly heads were indeed designed as a cheaper production and servicing alternative to the Hemi heads. For more details on the A-block and engine plant design and production, see the factory tour page.

A-blocks Are Not Performance Engines but were Designed for Economy

The A-block from its conception was in reality designed with both racing and economy in mind. The economy myth is like suggesting the small-block Chevrolet was designed for economy because they offered a two-barrel 283 and 327. As I explain in the 1956 section at the top of the page, Plymouth entered its new A303-powered 1956 Plymouth Fury in the 1956 NASCAR Speedweeks at Daytona Beach and broke two world records in its class. That same year, Plymouth released a rare factory aluminum dual-quad intake manifold available through dealerships (see the intake-manifold page). The 1956 Plymouth Fury came factory with a performance package A303, and Plymouth built on the performance in 1957 and 1958 with the release of the “Dual Fury V-800” A318 available in the Plymouth Fury that featured performance internals and dual WCFB carburetors. Compared to Chevrolet’s 265/283, Buick’s 322, and Ford’s 292/312 of the time, the Fury equipped with A303 and then A318 were a force to be reckoned with. In 1959, Chrysler Corp shifted focus and stopped funding the small-block performance program and focused those efforts on the B and RB engines for stock car and drag racing until they began funding the small-block program again in the mid-1960s with the LA273 Super Commando followed by the LA340 to compete with the GM and Ford small blocks. Chrysler Corp’s abandonment of their small-block performance program in 1959 is a significant reason the factory and aftermarket industries never developed as many performance parts for the A318 as they did for the Chevy 327 and Ford 289 but instead developed a plethora of parts for the B and RB engines. Imagine the factory and aftermarket performance parts we would have for the A-block if Chrysler Corp followed Chevy’s and Ford’s small-block performance programs of the early 1960s and developed racing A326 engines and stuffed them in the 1960 Valiant to compete with the Corvette and Thunderbird and later the economy-body cars such as the Chevy II, Falcon, and Mustang.

Just like GM and Ford, at the same time Plymouth focused the Fury A-blocks on performance, they also offered 2-barrel, lower-performance versions tailored for commuter economy, and such an A318 won its class in the 1957 Mobilgas Economy Run. The smaller 318 displacement and strong torque numbers made the A-block an obvious choice for an economy V8 in Chrysler Corp’s lineup by the early 1960s when a customers next options were gas-guzzling B361, B383, and RB413.

Industrial and Truck Engines Are Thicker Castings and the Best for Performance Builds

Garage legend has it that the industrial and truck versions of the the A318 are the strongest cores to start with for building a performance A-block, but somewhere along the telephone wires the facts were distorted. The reality is that all industrial and truck engines including the “Dash 3 Full Premium” package used the same block, cylinder heads, connecting rods, crankshaft, and many other components as the lowly 2-barrel car engine.

From 1959 – 1967, Chrysler Corporation’s Industrial Engine Division produced the “H-Series” of industrial engines that included four distinct models: H318, HB318, HC318, and HT318 depending on the application. All industrial engines aren’t created equal, however. The “H” indicates a light-duty engine, HB medium-duty, HC high-compression, and HT heavy duty. The H318 and HC318 models were the most widely produced, and their internal components are nearly identical to the “Dash 1 Standard” package A318 used in cars and light trucks. The medium-duty HB318 was used in applications that required slightly more durability but are very similar to the H318. The heavy duty HT318 is the rarest of the industrial engines and were used primarily in heavy agricultural and construction applications. Similarly, most light-duty trucks received the “Dash 1 Standard” engine package that cars received with the “Dash 2 Semi-premium” packages optional. Only the heavy trucks starting at D400 and W300 models up came standard with the “Dash 3 Full-premium” package. The HT318 industrial and “318-3” heavy truck engines used “Full-premium” internal parts; I detail all the different components used in the Full-premium models on the engine specifications page and the industrial engine page.

Regardless of the premium internal components, all industrial and truck A-blocks used the exact same block and head castings, forged crankshafts (shot-peened only for the industrial HB318/HT318 and “Dash 3 Full-premium” trucks), forged rods, etc. as the “Standard” and “Semi-premium” engines. There is no practical benefit in seeking out and paying more for an industrial or heavy truck “Full-premium” engine as a core for a performance build since most of the internal components that made the “Full Premium” line special in its day (valves, timing set, bearings, etc.) are now inferior to modern parts that would go into a high-performance build. The shot-peened crankshaft of the industrial HB318/HT318 and “Dash 3 Full-premium” engines would be a nice addition to retrofit into an A318 performance build over a standard forged crankshaft, but the standard forged crankshaft is exceptionally strong despite not being shot-peened and will take a wild amount of force and RPM to damage. In essence, the “Dash 2 Semi-premium” and “Dash 3 Full-premium” engines are no different than the “Dash 1 Standard” engine when it comes to selecting a rebuildable core.

Throw Away that Junk Engine!

As early as 1956, hot rodders and racers began removing their A-blocks to replace them with the more powerful large-displacement 354 and 392 Hemis and eventually B-blocks, RB-blocks, and the 426 Street Hemi. In 1968 with the introduction of the LA340, people had even greater options to replace their A318 with a small block of larger displacement and higher performance. Performance LA parts that do not fit A-blocks–mainly the intake manifold and headers–were more readily available shortly after the LA273 was released in 1964, and with the discontinuation of the A-block and introduction of the LA318 in 1967, the A318 largely fell by the wayside with performance enthusiasts. Once aftermarket iron and eventually aluminum LA cylinder heads came on the market, there was even more reason for people to ditch the A-block. Due to all the engine swapping and streets and swap meets lined with free A-blocks awaiting the junkman, myths started and have perpetuated that the A-block is a terrible engine design and cannot produce power on a reasonable budget. Going up against a 450 or 600 HP A-block 390, 402, or 408 stroker turning 7,000 rpm at the track might change one’s perception or at least give them a run for their money down at the traps. A-blocks in fact have strong block and head castings with less core-shift than other engines, thick cylinder walls that can often be overbored .090″ to accept 4″ pistons, factory forged crankshaft and rods, full-floating pistons, a very efficient and advantageous combustion chamber design, and when equipped with large valved and fully ported flow solid numbers compared to what the combustion dynamics require. The main cost differences between building a performance A-block and LA are the intake manifold, headers, pistons, valves, camshaft, and rocker arms to where a 500 HP A-block may cost around $2,000 more on average than a 500 HP LA with comparable parts. If the dollar amount per HP is the most important factor to the builder, the LA easily wins out, but then the LA would lose out to building a stroker RB which costs even less per HP. Most people I know who build A-blocks think the additional money is worth the uniqueness of building the engine and enjoying the results both aesthetically and in performance.

The Poly 318 is a “Wide-block” and Larger than an LA and B/RB!

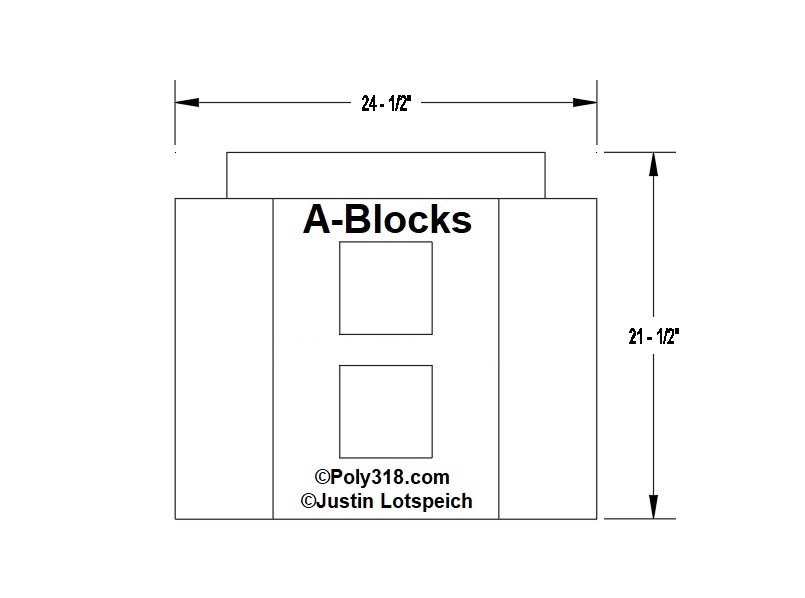

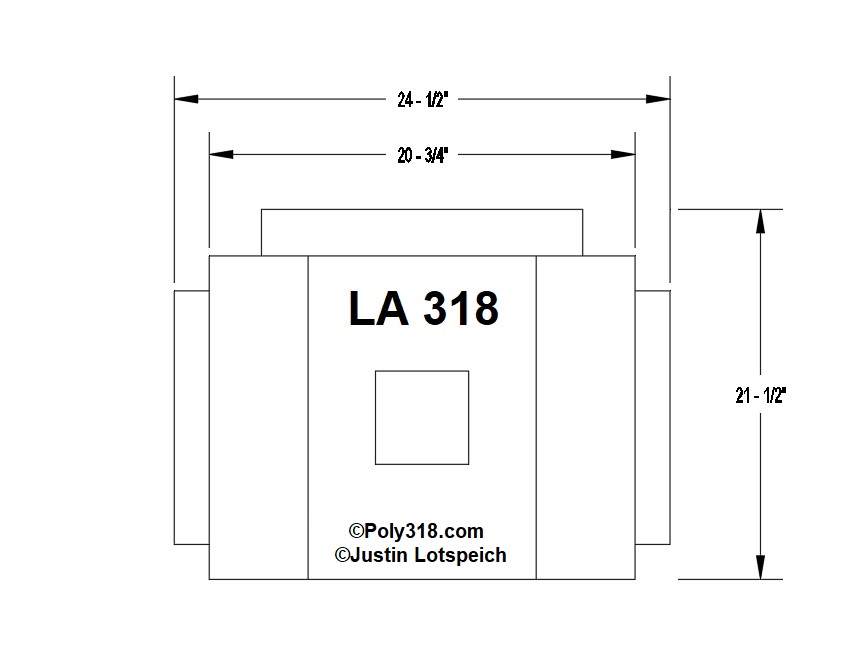

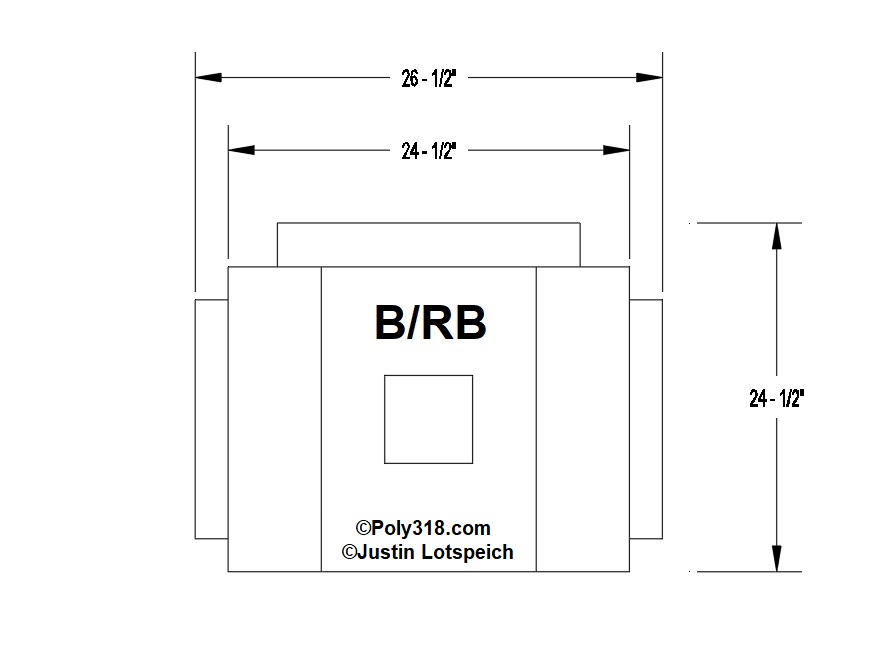

I regularly come across forum posts of someone enthusiastically interested in installing an A-block in a vehicle just to get naysayer responses, “Good luck fitting it. Those wide-block 318s are wider than a 440!” No they aren’t, and the blocks in fact are not wider than an LA273/318/340. The “wide-block” is very similar to the misused “semi-Hemi” moniker in that while it is inaccurate, people continue using it regardless of its inaccuracy. But the moniker has real-world consequences since I have run across multiple people at cruise nights, car shows, and the race track who look at an A-block engine and reminisce about how they always liked the look of an A-block over an LA but that they went with an LA engine in their vehicles because people called the A318 a “wide-block” suggesting it is not compatible with LA K-members/crossmembers and motor mounts when it in fact can be. The A318 and LA318 engine blocks are nearly identical to where most people would not tell them apart side by side, and an A-block block will bolt directly into a vehicle equipped with LA motor mounts. The difference is in the width of the cylinder heads and valve cover placement due to the poly combustion chambers and canted valves, which creates an optical illusion. I have measured a 1966 A318 and 1968 LA318 with factory valve covers side by side, and the A318 valve cover at the widest protrudes 1-7/8″ horizontally more on each side (total of 3-3/4″) than the LA valve covers, but there is more to explain about this measurement (Figures 7a – 7b). While the outside valve cover to outside valve cover width is 3-3/4″ wider on the A-block, both the A318 and LA318 are the exact same width overall at the widest point of 24-1/2″ from outside of factory exhaust manifold to outside exhaust manifold. The A318 valve covers extend horizontally about plumb with the exhaust manifolds when dropping a plumb bob, whereas the LA (and B/RB) valve covers stop about plumb with the exhaust gasket flange on the heads to where the exhaust manifolds stick out past the valve covers. This visual difference when standing in front of the engines and not seeing the exhaust manifolds on an A-block but seeing them on an LA gives the A318 an optical illusion of being overall wider and larger than an LA. The other optical illusion comes when comparing the A-block to a B/RB that doesn’t have exhaust manifolds/headers installed. I have measured and detailed in Figure 7c a B/RB to show that the A-block is the same width from outside valve cover to outside valve cover as the B/RB from outside valve cover to outside valve cover, which may lead one to claim the blocks are the same width. Install the B/RB exhaust manifolds/headers that protrude past the valve covers, and the B/RB is easily distinguishable as wider than the A-block. If someone wants advice on using an A-block in their vehicle, especially an A-body car, I would suggest they focus mainly on any chassis/body/accessories higher up in the engine compartment to see if there will be clearance issues with the A-block valve covers since they protrude more than the LA that might be coming out of the vehicle. The next area to examine is the steering system since LA engines in A-body cars were often offset to the right and used a unique left exhaust manifold that brought the manifold up beside the valve cover versus to the side and down in order to clear the steering. If the A-block is replacing an early Hemi, Hemi-block poly, or B/RB, there should be plenty of clearance.

Those Boat-anchor A-blocks Are Heavier than a 440!

Mopar’s marketing team did their job very well advertising the “Light A” LA273 as the lightest Mopar V8 ever made at the time to where it’s a common myth that the A-block is heavier than an RB. What Mopar neglected to publicize was what some Mopar sleuths, myself included, have confirmed by actually weighing parts. All in all, a factory A318 is between about 31 and 60 lbs. heavier than a factory LA318 depending on intake, timing cover, water pump, and accessories used. The heaviest A-block is the A318 with a “Dual Fury V800” 2×4 intake, cast iron timing chain cover, and cast iron water pump, which I own and weighed. The engine loaded from oil pan to carburetors, pulleys to rear crank flange (without alternator, power steering, A/C compressor) weighs 561 lbs., which is about the same as an LA360 and about 100 lbs. lighter than an RB440. Next time I have the opportunity to disassemble a B or RB, I intend on weighing its components and adding them to the list. Here’s the weight breakdown of parts that are unique to the A-block and LA that I weighed and corroborated with two other people’s measurements, although there is minimal standard deviation due to our different scales used.

- A318 bare block: 192 lbs.

- LA318 bare block: 169 lbs.

- Difference: 23 lbs.

- A318 heads (w/ valves installed, no rockers): 110 lbs.

- LA318 heads (w/ valves installed, no rockers): 102 lbs.

- Difference: 8 lbs.

- A318 pistons: 10.55 lbs.

- LA318 pistons: 10.42 lbs.

- Difference: 0.13 lbs.

- Total difference: the A318 is about 31 lbs. heavier than the LA318 when comparing these parts. There will be more difference depending on if the timing cover, water pump, and intake manifold are iron or aluminum, but we are talking about the difference between about 30 lbs. in these parts.

Conclusion

By working through the history and some of the misconceptions about the A-block, I hope to have educated those interested and set some of the record straight for those who appreciate accuracy. There are of course logical, reasonable arguments for running one engine over another engine–and the A-block will not fit everyone’s purpose–but the myths above unaddressed can cloud the options when making a decision. The A-block was a pivotal engine family that out of it grew the B, RB, and LA that would power millions of vehicles and win tens of thousands of races over two-and-a-half decades before the engine family once again evolved into the Magnum lasting into the 21st century.

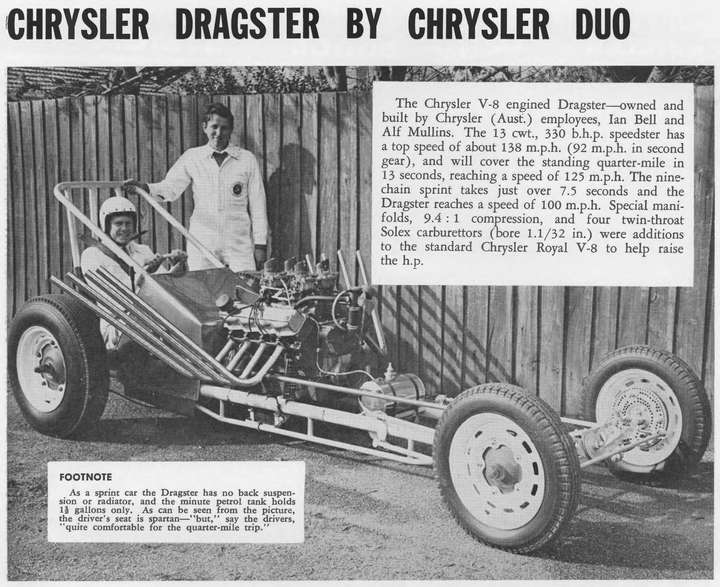

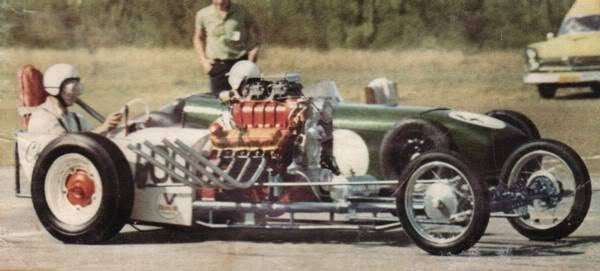

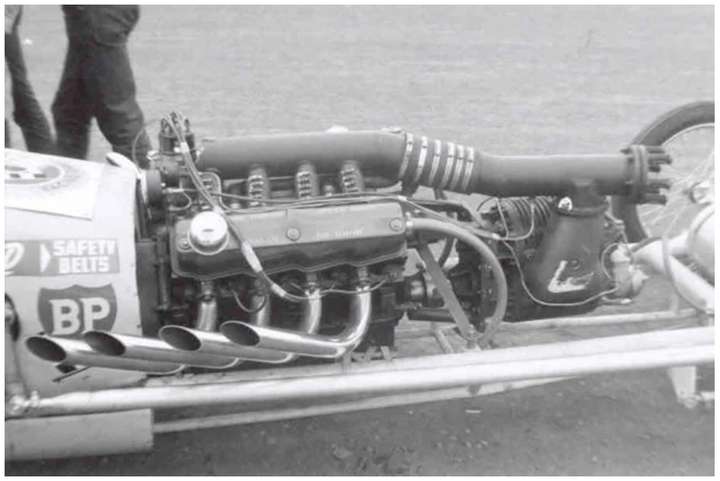

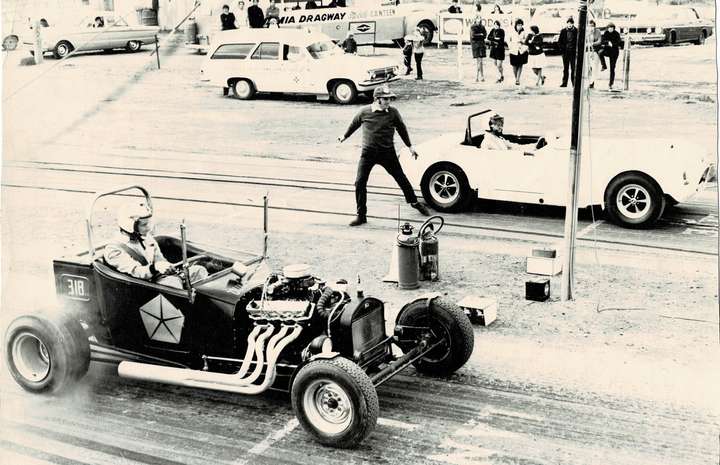

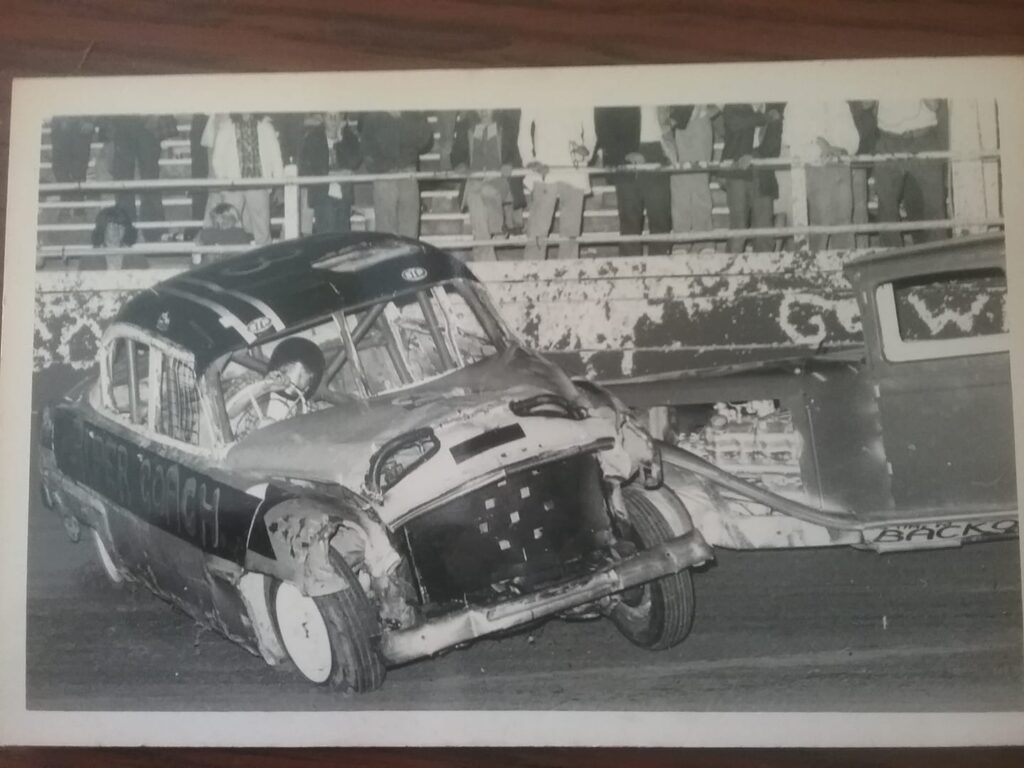

Vintage Hot Rod A-blocks

Please send in your vintage A-block photos!